Perspectives is an opportunity for Fellows and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays. IPE/BC Fellows hold a range of views and interests relative to public education.

Are Private Schools Better than Public Schools?

Perception Versus Reality

By E. Wayne Ross

Last year the BBC ran a story with the headline “How Canada Became an Education Superpower.” The BBC pointed out that Singapore, South Korea and Finland usually get mentioned as the world’s top performing education systems, “but with much less recognition, Canada has climbed to the top tier of international rankings.”

Whenever the OECD releases the Program for International Student Assessments (PISA) results, breathless reporting usually follows. There are many reasons to be skeptical of international rankings based upon a single test given to 15 year-olds.

Despite its international “superpower” status, a majority of Canadians don’t believe their public schools measure up to private schools. Less than seven percent of Canadian students attend private schools, but the majority of Canadians believe private schools provide a better education than public schools. In a 2012 Ipsos-Reid poll, 58% of respondents stated they believe private school education is better than public school education; 63% said they would send their children to private schools if they could afford it.

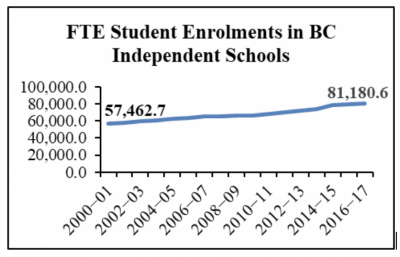

In British Columbia, there has been a 12% drop in public school enrolment since 2000. Meanwhile private school enrolments have increased from nine percent in 2000 to 13% in 2017, almost double the national average (Source: FISABC).

Between 2000–01 and 2016–17, the full-time equivalent (FTE) student enrolment in BC independent schools increased from 57,462.7 to 81,180.6. This is an increase of 41.3% (Source: BCTF)

So, if more parents in Canada and BC are choosing to send their children to private school is this an indication that private schools are really better than public schools? Not necessarily – indeed the research evidence suggests the answer is “no.” I will come back to this point in moment, but first let’s explore the conventional wisdom that private schools are better than public schools.

In BC, key factors that coincide with private school enrolment increases is an historic era of labour conflict, budget cuts, school closures and overcrowding in the public school system from 2000-2016.

Another factor related to increased private school enrolment is marketing. Extensive marketing campaigns touting a private school advantage cannot be underestimated.

In addition, while BC public schools were under a funding siege for the first 16 years of this century, private schools were enjoying significant funding increases and a wealth of positive (and free) press from publication of school ranking schemes, which consistently placed private schools at the top.

Between 2000–01 and 2016–17, funding for BC independent schools increased by 95.9%. This is larger than student enrolment increases by 54.6%, and larger than funding increases for public schools by 90.0%. (Source: BCTF)

All of these factors feed the idea there is a private school advantage.

But, reality is more than appearances and focusing exclusively on appearances—on the evidence that strikes us immediately and directly—can be misleading. This is particularly true when we examine school rankings because private schools’ higher average test scores are at the heart of the conventional belief that private schools are better than public schools, along with their typically well-funded programs.

Anyone who scrolls through the rankings of BC schools will find evidence that students who attend private schools have better on average academic performance than public school students. But the key question is to what degree do private schools actually produce those results?

There is a growing body of research evidence that attempts to answer this question.

In 2011, OECD’s analysis of PISA results found that while students in private schools tended to outperform their public school peers, the difference was primarily the result of the higher socio-economic status of private school families.

“Students in public schools in a similar socio-economic context as private schools tend to do equally well,” according to the OECD report, which concluded that “there is no evidence to suggest that private schools help to raise the level of performance of the school system, as a whole” (OECD, Private schools: Who benefits?)

In their 2013 book, The Public School Advantage, University of Illinois researchers Sarah Theule Lubienski and Christopher Lubienski found that compared to private schools students, public school students performed the same if not better on achievement tests once demographic factors were taken into account.

Statistics Canada echoed these findings in a 2015 report, which found students in Canadian private schools have more educational success than their public school counterparts because of their socio-economic characteristics, not because of private schools themselves.

The StatsCan report identifies two factors that consistently account for differences between public and private school student academic outcomes. “Students who attended private high schools were more likely to have socio-economic characteristics positively associated with academic success and to have school peers with university-educated parents … School resources and practices accounted for little of the differences in academic outcomes” (Statistics Canada: Academic Outcomes of Public and Private High School Students: What Lies Behind the Differences?)

And, in a study published last month, University of Virginia researchers Robert C. Pianta and Arya Ansari examined the extent to which enrolment in private schools between kindergarten and grade nine was related to students’ academic, social, psychological and attainment outcomes at age 15. This longitudinal study of over one thousand students concluded:

“… children with a history of enrollment in private schools performed better on nearly all outcomes assessed in adolescence. However, by simply controlling for the socio-demographic characteristics that selected children and families into these schools, all of the advantages of private school education were eliminated.”

In addition, Pianta and Ansari found no evidence to suggest that low-income children or children enrolled in urban schools, benefited from private school enrolment.

Are private schools really better than public schools? Conventional wisdom may say they are, but the evidence suggests that is a myth.

Parents send their children to private schools for a variety of reasons that make sense for them. But, there is substantial and growing evidence that there is no value-added in private school education.

For more research-based resources on private schools see “Resources on Private Schools” by National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado.

E. Wayne Ross is a Professor of education at the University of British Columbia and an IPE/BC Board Member and Fellow.

Technology on its own cannot improve education systems and require other elements to be functional and focus on the effective use of technology. Yet our education systems continue to invest in technology, often based on what seems to be the latest and greatest. How do we address this so that the education system can achieve the results we expect with current and innovative technology developments? How do we avoid our education becoming too influenced by the latest technology development and ‘carpet-baggers’ peddling the latest technology with promises to revolutionize education?

Technology on its own cannot improve education systems and require other elements to be functional and focus on the effective use of technology. Yet our education systems continue to invest in technology, often based on what seems to be the latest and greatest. How do we address this so that the education system can achieve the results we expect with current and innovative technology developments? How do we avoid our education becoming too influenced by the latest technology development and ‘carpet-baggers’ peddling the latest technology with promises to revolutionize education? Obviously, anything that makes the well-heeled pay a little extra or tames profit-taking in the housing market should benefit the push for increased affordability.

Obviously, anything that makes the well-heeled pay a little extra or tames profit-taking in the housing market should benefit the push for increased affordability.

Thousands of apps for education have already been created. Development costs are often covered by venture capitalists. They invest in app development with the hope that future profits will provide a return on investment when it captures a significant number of users. In many cases, the return is the sale of information about the teachers and students using the app. It is the users themselves who are the source of profits when their data is sold.

Thousands of apps for education have already been created. Development costs are often covered by venture capitalists. They invest in app development with the hope that future profits will provide a return on investment when it captures a significant number of users. In many cases, the return is the sale of information about the teachers and students using the app. It is the users themselves who are the source of profits when their data is sold. The benefits are not only apparent in academic indicators like test scores and grades, but also longer term educational and life outcomes like high school completion, less juvenile criminal behaviour, and increased post-secondary enrollment.

The benefits are not only apparent in academic indicators like test scores and grades, but also longer term educational and life outcomes like high school completion, less juvenile criminal behaviour, and increased post-secondary enrollment.