Perspectives is an opportunity for Fellows and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays. IPE/BC Fellows hold a range of views and interests relative to public education.

Accountability for BC Schools: A Charter Compact for British Columbians

by Dr. Dan Laitsch

Accountable to whom and for what?

In some form this question has been asked of our institutions since at least the early 1700s. In the context of today’s public schools, the question is of particular importance.

Public schools are faced with a wide array of accountability demands. For example, many educators feel a responsibility to the fields in which they teach—that is, they are accountable to the subject-matter they teach for upholding particular curricular standards. Teachers may also feel accountable to students for their learning; to parents for the well-being of their children; to their colleagues for the performance of the school.

Teachers may be asked by colleges and universities to be accountable for preparing students for post-secondary learning; by employers for preparing a skilled work force; and by judicial authorities for preparing law-abiding citizens. In the current context (of pandemic), educators have been asked to take on accountability for the physical and mental health of students as well. In short, schools have many constituencies they serve and for many diverse reasons, but most of these groups have very little agency to inform educator practices. Instead, government has largely taken on that authority.

learning; by employers for preparing a skilled work force; and by judicial authorities for preparing law-abiding citizens. In the current context (of pandemic), educators have been asked to take on accountability for the physical and mental health of students as well. In short, schools have many constituencies they serve and for many diverse reasons, but most of these groups have very little agency to inform educator practices. Instead, government has largely taken on that authority.

Historically schools were funded and governed by locally elected school boards. In many ways this made accountability much simpler as educator accountability was quite local and close to stakeholders. As Canada grew, so too did the number of school boards and the complexity of the system. When the Constitution Act was enacted in 1867, education came to rest at the provincial, rather than local (or Federal), level. Since that time, local schools boards in BC have been increasingly regulated and consolidated by the Province (going from around 650 school districts in 1945 to 57 today) and now have only limited autonomy under the provincial government (focusing primarily on budget management and local application of provincial policies).

Over this period, we’ve also seen teacher training moving to universities and the beginning of professionalization, which brought with it its own accountability concerns. In some cases, tensions arose between school boards and teachers, ultimately leading to the formal unionization of teachers (and even greater centralization of provincial control). Today’s conversations frequently emphasize accountability to these centralized sources—government and teacher certification systems, and teachers’ professional unions.

The end result of the centralization and professionalization of education has been a distancing of public education from the community it serves. Indeed, when you look at the public opinion data on schools, you find that the public is generally quite supportive of their local schools and the schools their children attend, but that support diminishes the further away from the community you get (i.e., less favourable ratings of other school districts, schools at the state/provincial level, or schools nationally).

This separation of schools and communities is a problem. The provincial government has worked to address the problem in part through the establishment of Parent Advisory Committees and regular parent satisfaction surveys. Here too, however, power sharing between the Province and parents remains largely symbolic, and has in many ways been used to further constrain educator authority. Across all aspects of governance, in BC the Provincial government has centralized almost all authority regarding the public education system.

This separation of schools and communities is a problem. The provincial government has worked to address the problem in part through the establishment of Parent Advisory Committees and regular parent satisfaction surveys. Here too, however, power sharing between the Province and parents remains largely symbolic, and has in many ways been used to further constrain educator authority. Across all aspects of governance, in BC the Provincial government has centralized almost all authority regarding the public education system.

This centralization has left very little ability for stakeholder groups (teachers, parents, students, or the broader public) to hold the government to account for the way it manages the system. Teachers have some ability to hold government to account through the collective bargaining process—but as we saw in the early 2000s that process can be corrupted (when the Liberals illegally stripped teachers of their collective rights), and costly to enforce (as teachers were forced into a decade long series of court battles). The ability of British Columbians (as the “public” in public education) to inform the government about the outcomes they want from their education system is even more limited.

Returning to our original question, then, accountable to who and for what, in education Government is weakly accountable to teachers, and even less accountable to the public. Accountable “for what” is largely left undefined. Many governments, BC included, have fallen back on very narrow curricular goals (literacy and numeracy) supplemented by occasional hot button issues (such as graduation rates), generally measured by simplistic large-scale tests and surveys.

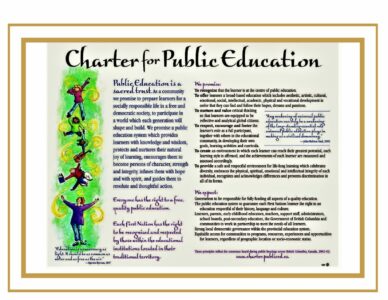

In an effort to better define the “for what”, and strengthen the role of the public in the accountability conversation, in 2003 the BCTF decided to ask British Columbians directly about what they wanted from their public school system. A panel of five British Columbians launched a lengthy public consultation process that resulted in the Charter for Public Education. While the Charter process was initiated by teachers through their provincial union the BCTF, it was independently organized and governed.

For five months the panel traveled the province to gather statements from BC residents (students, parents, educators, business people, politicians, and anyone expressing an interest in education in BC). In 42 communities across BC, in large and small cities, rural and urban settings, and throughout the province by e-mail, the panel solicited testimony from British Columbians. The process was focused on aspirational outcomes for BC students and so focused around four over-arching questions:

politicians, and anyone expressing an interest in education in BC). In 42 communities across BC, in large and small cities, rural and urban settings, and throughout the province by e-mail, the panel solicited testimony from British Columbians. The process was focused on aspirational outcomes for BC students and so focused around four over-arching questions:

“What is an educated person?”

“Which of the characteristics [of an educated person] are developed through the public schools?”

“What is an educated community?”

“What are the principles of public education?”

A total of 608 British Columbians responded and the data analyzed included not just presentations and submissions, but the conversations around them. The material was synthesized and analyzed by the panelists for core themes and issues, and this initial analysis and conclusions were further reviewed and commented on by a parent, trustee, teacher and university faculty member selected from hearing participants. Their feedback then informed the final document: The Charter for Public Education.

The Charter was organized into four sections, an overarching preamble, Rights, Promises and Expectations. While the content of these sections are not the focus of this article, the Charter lays out what the public in BC expects of its education system and the responsibilities of stakeholders in ensuring the promise of education is realized. It helps identify the outcomes Government should be held accountable for, and it gives educators an aspirational vision to work toward.

The Charter for Public Education currently rests with the Institute for Public Education/BC. We see the Charter as a charge to Government, Educators, and the public, and a lens through which we can better understand how our schools are doing, and how our government is fulfilling its Constitutional mandate to educate BC’s citizens.

In this light, we also see the Charter as a living document that can be examined and revised as our society grows and evolves. In looking at the Charter today, we have questions about the place of diverse learners and Indigenous students in the document; the place of equity, diversity, and inclusion in BC; and are asking what it means to highlight values espoused by Egerton Ryerson on education (“Education is as necessary as the light. It should be as common as water, and as free as air”)—a strong advocate of public education who also helped create the residential school system and opposed the education of women beyond elementary school.

For accountability to be realized, it must be based in constant reflection, a common understanding of who is engaged in the work, what they are trying to do, and the capacity they have to do that work well. It must be based in the current social context, but looking toward an aspirational future state. We believe the Charter offers us a strong foundation for this work, but only to the extent that it can engage the broader public in holding government to account for the system it controls. We invite you to join us in envisioning what a system based in the Charter should look like now, where we should be moving our schools in the future, and how we can get there together.

If you’re interested in contributing to our work, please contact us!

Dan Laitsch is the Chairperson of the Institute for Public Education’s Board of Directors. He is a founding director for the Centre for Study of Educational Leadership, Associate Professor at SFU and Director of the SFU Surrey Campus Liaison, Faculty of Education.