IPE/BC is an independent, non-partisan organization, however we recognize that IPE/BC Fellows and guest authors hold a range of views and interests relative to public schools, education issues, and the political landscape in BC. Perspectives is an opportunity for Fellows and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays.

The Impact of the New Rights on the Privatization of Education

Andrée Gacoin

November 25, 2024

The conservative discourses of the new Rights, and their impact on education, was top of mind in October 2024 as BC went to the polls to elect a new provincial government. In Canada, education is the mandate of provincial governments and, while education is not always an  election issue, this particular race was dominated by harmful and hateful rhetoric that sought to control and further privatize education. This included:

election issue, this particular race was dominated by harmful and hateful rhetoric that sought to control and further privatize education. This included:

-Censoring of classroom materials. In media interviews, as well as the party platform, the Conservative Party of BC critiqued educational materials for being politically biased and promoting (progressive) ideologies.[i] The popularity of this view can be seen in the increase of “book challenges” across Canada. These challenges are when individuals or group seek to remove books from school libraries or restrict them to certain audiences. Books that are inclusive of diverse gender identities and sexual orientations, as well as books by Indigenous, Black and authors who identify as People of Colour have all been challenged.[ii]

-Attacking social justice and rights-based approaches as “indoctrination” and seeking to control teachers’ professional autonomy. The Conservative Party’s agenda built on moral panics that have mobilized parent groups across the province, panics seen in previous elections for school trustees as well.[iii] For example, groups have gathered outside schools, and targeted individual teachers, to protest the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity in the curriculum.[iv] Complaints have been made to the Teacher Regulation Branch, a body that governs the professional conduct of teachers, related to teacher’s curricular decisions related to social justice issues.

-Being explicitly anti-union. The Conservative platform focused on terms such as “open procurement” and “qualified” workers and critiqued government for being overly influenced by unions. This is part of a broader fiscal conservatism that promotes reduced government spending, free markets, free trade, and privatization.

–Increased funding for private schools. In BC, many private schools (called “Independent Schools”) receive government funding at either 50% or 35% of their local public school district rate. The Conversative Party of BC argues that private options are necessary because of parent’s concerns about the “ideologies” being taught in public schools.

While the Conservative Party of BC did not ultimately win (barely),[v] they have formed the official opposition and there was overwhelming support for the Conservatives in many parts of the province. Their ideas for education are reflected in the ongoing advocacy of right-wing Think Tanks, such as the Fraser Institute, that champion education reforms “to achieve better value for money and improved results for both students and taxpayers.”[vi] Proposed measures include returning to a “back-to-the-basics” curriculum, increasing student testing for accountability, and establishing charter schools in the province.

support for the Conservatives in many parts of the province. Their ideas for education are reflected in the ongoing advocacy of right-wing Think Tanks, such as the Fraser Institute, that champion education reforms “to achieve better value for money and improved results for both students and taxpayers.”[vi] Proposed measures include returning to a “back-to-the-basics” curriculum, increasing student testing for accountability, and establishing charter schools in the province.

The political landscape in BC reflects the rise of conservative politics across Canada. In the province of Ontario, for instance, there is a populist provincial leader who has consistently underfunded public education for six years, leading to larger class sizes, decaying buildings, and fewer supports and services for students.[vii] In Quebec, the rise of conservatism can be seen in politicians who openly and proudly push an anti-union agenda and attempt to convince the public that unions are to blame for the failing of public services. This is coupled with xenophobic rhetoric that blames immigrant populations for problems within the province.[viii] Nationally, the leader of the Conservative Party is seeking to be the next Prime Minister of Canada. He is a self-described “champion of a free market,” believes in “limiting government” and posits that schools should “stick to teaching math, reading and writing.”[ix] Public opinion polls indicate that he would win if the Canadian election was held today.[x]

As illustrated in the case of the BC election, these conservative political parties are linked to the rise of the “parental rights” movement in Canada – a movement that embodies the many links between far-right ideologies and interest in education privatization. In BC, for example, the attacks have been focused on a program called SOGI 123, which supports teachers to make schools safer and more inclusive for students of all sexual orientations and gender identities. Contrary to the arguments of the new Rights, research illustrates the positive impact of this program. A recent evaluation of SOGI 123, done by researchers at the University of British Columbia, found that the program decreased bullying and sexual orientation discrimination for both LGBT+ and also for heterosexual students.[xi] However, conservative groups, taking up the language of “choice” in education, continue to attack the program (and those who teach it) as “indoctrinating” kids and promoting “radical ideologies.”

As illustrated in the case of the BC election, these conservative political parties are linked to the rise of the “parental rights” movement in Canada – a movement that embodies the many links between far-right ideologies and interest in education privatization. In BC, for example, the attacks have been focused on a program called SOGI 123, which supports teachers to make schools safer and more inclusive for students of all sexual orientations and gender identities. Contrary to the arguments of the new Rights, research illustrates the positive impact of this program. A recent evaluation of SOGI 123, done by researchers at the University of British Columbia, found that the program decreased bullying and sexual orientation discrimination for both LGBT+ and also for heterosexual students.[xi] However, conservative groups, taking up the language of “choice” in education, continue to attack the program (and those who teach it) as “indoctrinating” kids and promoting “radical ideologies.”

Across Canada, this “moral panic” becomes a weapon against public education in two key ways. Firstly, it is used as a political rallying call to “take-back” public education, such as by electing morally conservative trustees on public school boards. Secondly, it legitimizes parent “choice” to opt-out of public education and mobilizes this “choice” to increase the privatization of public services.

[i] See for example: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-conservatives-election-eductation-policy-1.7351918 and https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/sogi-123-sexual-education-b-c-election-2024-1.7333988

[ii] https://www.teachermag.ca/post/book-challenges-protecting-diversity-in-our-llcs

[iii] See for example: https://www.comoxvalleyrecord.com/community/courtenay-school-board-trustee-candidate-distributing-anti-sogi-material-1636411

[iv] See for example news coverage, and teachers’ responses, at: https://pressprogress.ca/surrey-teachers-speak-out-against-misinformation-around-2slgbtq-education-in-bc-schools/

[v] 47 seats in the BC Legislative Assembly are needed to form a majority government. The center-left National Democratic Party (NDP) won those 47 seats, just securing the majority. The Conservative Party of BC won 44 seats and the BC Green Party won 2 seats.

[vi] https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/k-12-education-reform-in-british-columbia

[vii] See a statement from the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation (OSSTF) here: https://www.osstf.on.ca/en-CA/news/new-coalition-announces-coordinated-response-to-ford-government.aspx

[viii] See for example: https://cultmtl.com/2024/11/quebec-mna-haroun-bouazzi-accuses-colleagues-of-recurring-xenophobia-polarizing-lie-or-uncomfortable-truth/

[ix] https://www.conservative.ca/pierre-poilievre/

[x] https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/no-trump-bump-liberals-us-election

[xi] See: https://www.saravyc.ubc.ca/2024/10/09/report-evaluation-of-sogi-123-in-bc/

Dr. Andrée Gacoin is the Director of the Information, Research and International Solidarity Division at the BC Teachers’ Federation and an IPE/BC Fellow. Her research focuses on developing a unique, in-depth and contextualized exploration of education in BC from the perspective of teachers. Andrée is particularly interested in using research as advocacy to uphold and strengthen an inclusive public education system.

Here’s an idea: Let’s use unpaid labour in the form of captive public-school kids and their overworked, underpaid teachers, and heck, we can even make them compete for the privilege!

Here’s an idea: Let’s use unpaid labour in the form of captive public-school kids and their overworked, underpaid teachers, and heck, we can even make them compete for the privilege!

As a former Vancouver school trustee and its longest serving chairperson, I’m opposed to private businesses using schools to polish their public images. If they want to support schools, they can make a

As a former Vancouver school trustee and its longest serving chairperson, I’m opposed to private businesses using schools to polish their public images. If they want to support schools, they can make a

It’s time to let parties and candidates know what you want to see if they want your vote, donation, or volunteer time. If they want to put a sign in your window or on your lawn, demand to know what they’re committing to for public education. I’ll be letting my candidates know that having among the lowest per-student funding in Canada doesn’t cut it. I want to know when they’re going to complete all outstanding school seismic upgrades.

It’s time to let parties and candidates know what you want to see if they want your vote, donation, or volunteer time. If they want to put a sign in your window or on your lawn, demand to know what they’re committing to for public education. I’ll be letting my candidates know that having among the lowest per-student funding in Canada doesn’t cut it. I want to know when they’re going to complete all outstanding school seismic upgrades. school land deemed ‘surplus.’ The BC Liberals closed 267 schools during their tenure, and K-12 funding fell to all-time lows. They also created a program (that still exists) to sell property deemed ‘surplus.’

school land deemed ‘surplus.’ The BC Liberals closed 267 schools during their tenure, and K-12 funding fell to all-time lows. They also created a program (that still exists) to sell property deemed ‘surplus.’ The trouble of course is that much of this land isn’t really surplus and is almost always needed in the future. With the ever-upward march of land values, school properties that are sold are gone forever- unattainable and unaffordable when needed back. Where land values are highest, the pressure to sell land is greatest, and the public has the greatest amount to lose in this folly. In Vancouver, the site of the current Wall centre, worth likely hundreds of millions, was formerly the site of a school.

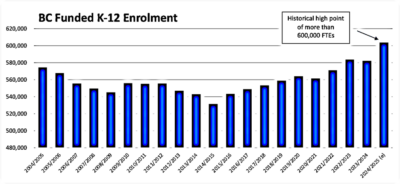

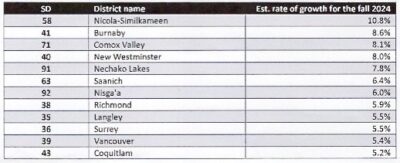

The trouble of course is that much of this land isn’t really surplus and is almost always needed in the future. With the ever-upward march of land values, school properties that are sold are gone forever- unattainable and unaffordable when needed back. Where land values are highest, the pressure to sell land is greatest, and the public has the greatest amount to lose in this folly. In Vancouver, the site of the current Wall centre, worth likely hundreds of millions, was formerly the site of a school. In Surrey district, where the population of school-aged children is exploding, the lack of land set aside for new schools is felt keenly as the district packs more and more students into existing schools – many in portable buildings. In Vancouver, where land values are high, schools are in poor repair and some buildings have excess capacity, largely created by the lack of family housing stock in the city, something likely to change in the future as the calls for increased density come from all political camps. North Vancouver district closed and sold many elementary schools during the last twenty years and parents in the district are now desperate for spaces as the density of school-aged children increases past capacity and projections.

In Surrey district, where the population of school-aged children is exploding, the lack of land set aside for new schools is felt keenly as the district packs more and more students into existing schools – many in portable buildings. In Vancouver, where land values are high, schools are in poor repair and some buildings have excess capacity, largely created by the lack of family housing stock in the city, something likely to change in the future as the calls for increased density come from all political camps. North Vancouver district closed and sold many elementary schools during the last twenty years and parents in the district are now desperate for spaces as the density of school-aged children increases past capacity and projections.

that provincial law meant that fees could not be charged. The court case was successful in 2006.

that provincial law meant that fees could not be charged. The court case was successful in 2006. “shall consult with appropriate teachers, staff, staff committee, students and the Parents’ Advisory Council prior to establish the fee.” Do you recall that consultation last school year?

“shall consult with appropriate teachers, staff, staff committee, students and the Parents’ Advisory Council prior to establish the fee.” Do you recall that consultation last school year? financial hardship and how the waiver can be obtained. The policy is supposed to be fair, consistent and confidential. You can find how your district provides this in the district policy or ask the school principal.

financial hardship and how the waiver can be obtained. The policy is supposed to be fair, consistent and confidential. You can find how your district provides this in the district policy or ask the school principal. The NATO-induced commitment is not something prescribed by law. Nor is it a treaty commitment. It is a political deal hashed out within a supranational military organization that hasn’t been elected by anyone. It is very telling that when the Prime Minister announced his recent 2% timetable, it was not done in parliament, or even within Canada – it was done in a European forum in front of politicians, bureaucrats, generals and defense pundits – and covered by a mainstream media that increasingly functions as echo chamber for military-industrial interests. This is the group calling the defense spending shots and the group Canada has decided to answer to.

The NATO-induced commitment is not something prescribed by law. Nor is it a treaty commitment. It is a political deal hashed out within a supranational military organization that hasn’t been elected by anyone. It is very telling that when the Prime Minister announced his recent 2% timetable, it was not done in parliament, or even within Canada – it was done in a European forum in front of politicians, bureaucrats, generals and defense pundits – and covered by a mainstream media that increasingly functions as echo chamber for military-industrial interests. This is the group calling the defense spending shots and the group Canada has decided to answer to.

resource shortage and funding insecurity?

resource shortage and funding insecurity? As the IPE quoted UNICEF Canada in our

As the IPE quoted UNICEF Canada in our

Having good food available at school would reduce busy families’ financial and time pressures, expose kids to a wide range of healthy foods, remove the stigma of current food programs that are targeted only to kids from poor families and support local food production.

Having good food available at school would reduce busy families’ financial and time pressures, expose kids to a wide range of healthy foods, remove the stigma of current food programs that are targeted only to kids from poor families and support local food production. There have been many prominent Indigenous scholars of educational discourses over the past number of years who have made clear the need for changes in the way mainstream educational practices and curriculum include and address Indigenous students, their cultures and histories within schools (Battiste, 2004; Dion, 2008; Donald, 2009; Schick & St. Denis, 2004; St. Denis, 2011). They point to the fact that colonial logics and agendas have excluded, reduced, distorted and erased Indigenous cultures, languages and knowledges in curriculum for decades. This is important when we think about the many Canadians who have become teachers having risen through the very systems of education that were perpetuating ignorance and misunderstanding. Indeed, in my early days of teaching Indigenous education to pre-service teachers, many expressed anger and dismay when it became clear to them what was intentionally not taught to them in schools.

There have been many prominent Indigenous scholars of educational discourses over the past number of years who have made clear the need for changes in the way mainstream educational practices and curriculum include and address Indigenous students, their cultures and histories within schools (Battiste, 2004; Dion, 2008; Donald, 2009; Schick & St. Denis, 2004; St. Denis, 2011). They point to the fact that colonial logics and agendas have excluded, reduced, distorted and erased Indigenous cultures, languages and knowledges in curriculum for decades. This is important when we think about the many Canadians who have become teachers having risen through the very systems of education that were perpetuating ignorance and misunderstanding. Indeed, in my early days of teaching Indigenous education to pre-service teachers, many expressed anger and dismay when it became clear to them what was intentionally not taught to them in schools. responses and thoughts in this process, even those who are most uncomfortable often find support in their learning, and inspiration in the insights of their classmates (Leddy, 2023).

responses and thoughts in this process, even those who are most uncomfortable often find support in their learning, and inspiration in the insights of their classmates (Leddy, 2023). resources to which they are exposed. But the best part is that Indigenous approaches to education demonstrably benefit all of our students, making the work of decolonizing and Indigenizing all the more pertinent and pressing (Restoule, 2017). When we teach with attention to Kirkness’s 4Rs of Indigenous education, respect, reciprocity, relevance, and responsibility, then we model what it means to build and maintain good relationships with ourselves, others, and what we must all learn together. When we use holistic frameworks, such as the Medicine Wheel, in our pedagogical and planning considerations, we can plan lessons and learning experiences that address our students as the intellectual, spiritual, emotional and physical beings that they are. And when we undertake to do the work of decolonizing ourselves, we become better at preparing our students for the world they will inherit, putting the Eurocentric practices of the past behind us where they belong.

resources to which they are exposed. But the best part is that Indigenous approaches to education demonstrably benefit all of our students, making the work of decolonizing and Indigenizing all the more pertinent and pressing (Restoule, 2017). When we teach with attention to Kirkness’s 4Rs of Indigenous education, respect, reciprocity, relevance, and responsibility, then we model what it means to build and maintain good relationships with ourselves, others, and what we must all learn together. When we use holistic frameworks, such as the Medicine Wheel, in our pedagogical and planning considerations, we can plan lessons and learning experiences that address our students as the intellectual, spiritual, emotional and physical beings that they are. And when we undertake to do the work of decolonizing ourselves, we become better at preparing our students for the world they will inherit, putting the Eurocentric practices of the past behind us where they belong. The bigger problem here comes down to the teacher increment ladder. Educators are underpaid for the nine to ten years it takes to reach full salary – the regular rate for the job. This encourages implementation of an extractivist approach to the use of educator labour. Extractivism is a concept developed by David Harvey, Veronica Gago, Nancy Fraser and others to describe power relationships which afford those in control the ability to confiscate or extract rising shares of value from their subordinates.

The bigger problem here comes down to the teacher increment ladder. Educators are underpaid for the nine to ten years it takes to reach full salary – the regular rate for the job. This encourages implementation of an extractivist approach to the use of educator labour. Extractivism is a concept developed by David Harvey, Veronica Gago, Nancy Fraser and others to describe power relationships which afford those in control the ability to confiscate or extract rising shares of value from their subordinates. which allow for the migration to other areas of work. Less stress? Better pay? Reduced feeling that your commitment to work is being used against you? Hey, why not make that move?

which allow for the migration to other areas of work. Less stress? Better pay? Reduced feeling that your commitment to work is being used against you? Hey, why not make that move? It’s time to think “outside the box” and look for innovative ideas to deal with a problem that is likely only to get worse. We can all support the call for more funding resources for public education but there is also a need to look at practical options for making better use of whatever resources are provided to support public schooling.

It’s time to think “outside the box” and look for innovative ideas to deal with a problem that is likely only to get worse. We can all support the call for more funding resources for public education but there is also a need to look at practical options for making better use of whatever resources are provided to support public schooling.