IPE/BC is an independent, non-partisan organization, however we recognize that IPE/BC Associates and guest authors hold a range of views and interests relative to public schools, education issues, and the political landscape in BC. Perspectives is an opportunity for Associates and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays.

Education Assistants play a critical role in inclusion

September 12, 2025

By Kirsten Daub

When people think about education assistants, they often picture someone giving a student some extra help with math or reading. And while that is certainly part of what an EA does, their role encompasses so much more.

In every classroom across British Columbia, education assistants play a critical role in ensuring all students get access to the quality public education. EAs ensure that all kids – including kids with diverse learning abilities or disabilities – can have meaningfully access to public education in this province.

We know that not everyone learns the same way. Education professionals are adept at modifying curricula to suit a variety of learning styles and needs – Individual Education Plans (IEPs). But in a classroom with a large number and wide range of students, without an EA, teachers struggle to meet the learning needs of all their students.

We know that not everyone learns the same way. Education professionals are adept at modifying curricula to suit a variety of learning styles and needs – Individual Education Plans (IEPs). But in a classroom with a large number and wide range of students, without an EA, teachers struggle to meet the learning needs of all their students.

EAs play a vital role in understanding the unique needs of students, making their IEPs work in the classroom context, and working with teachers to modify IEPs to respond to the unique needs of a student.

But EAs work goes far beyond implementing personalized learning strategies.

Kids are small versions of adults whose brains are still developing and often haven’t yet learned how to constructively express their feelings. Kids with neurodevelopment differences may need extra help with communication, social interaction and behaviour. EAs are experts in understanding what students are communicating with their behaviour and responding to that student’s needs.

It’s easy to get frustrated when we don’t feel understood. For some kids, that frustration becomes behaviour that’s disruptive or harmful to others. EAs have the specialized training and expertise to understand behaviour, support students in communicating their needs, managing those needs, offering emotional support to help students feel confident in the classroom, and facilitating interaction with other students and encouraging friendships.

interaction with other students and encouraging friendships.

In short, EAs are the key to fostering a truly inclusive education system for all students.

In an ideal world, every student who needed one would have an education assistant assigned to them. This is not our current reality.

Instead, EAs are often assigned multiple students to support. I’ve spoken with EAs who support four or five different students in one day. They are frustrated that they can’t spend more time with students, and they see first- hand that a growing number of kids are not getting what they need to succeed in the classroom.

Kids are getting frustrated, acting out and giving up.

Without a consistent level of support, EAs just can’t keep up with the needs of the students who need them to meaningfully experience public education. And when students’ needs aren’t met, that can make the role of an EA harder to fulfill. This is leading to EAs report experiencing stress and burnout trying to do a nearly impossible job.

School Districts across B.C. often struggle to balance budgets. Cuts to support staff are often how those budgets are balanced. In spring of 2025, for example, the Surrey School District faced a $16-million-dollar deficit. Part of the District’s response was to cut fifty EA positions. This can only mean that students who rely on EAs will have less support, and EAs will be stretched even more.

This is not a unique situation. School districts across the province need more funding to adequately staff classrooms. Many districts are struggling with recruitment of qualified EAs due to lack of hours and earning potential. As school districts make more cuts to balance budgets, the crucial work of EAs will become more unsuitable – EAs will suffer more burn out and leave the profession, and kid will have less support.

This is not a unique situation. School districts across the province need more funding to adequately staff classrooms. Many districts are struggling with recruitment of qualified EAs due to lack of hours and earning potential. As school districts make more cuts to balance budgets, the crucial work of EAs will become more unsuitable – EAs will suffer more burn out and leave the profession, and kid will have less support.

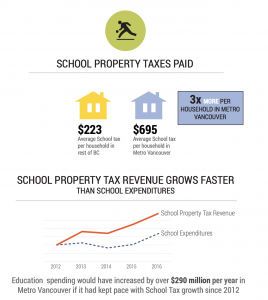

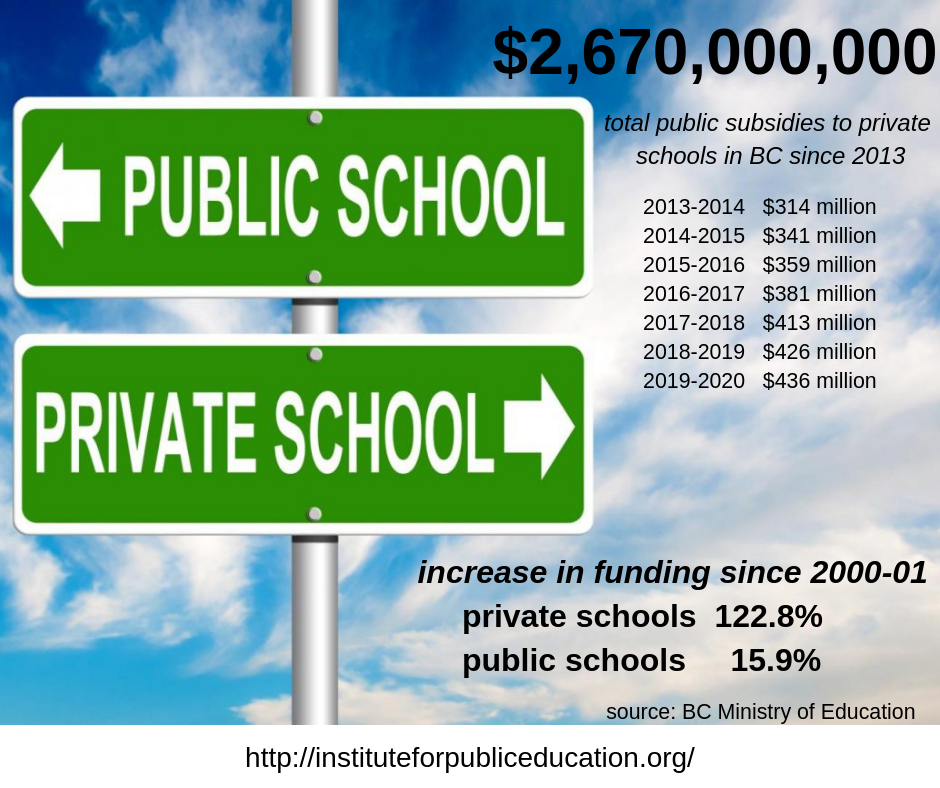

If B.C. is truly committed to inclusive public education, we need to make immediate and long-term investments. School operating grants as a percentage of the province’s GDP have decreased significantly since 1981.

We can do better for our kids.

Ensuring every student has the resources they need to succeed is an investment in stronger families, stronger communities and a better province. Most importantly, increased education public education spending is an investment in our kids – all our kids.

Kirsten Daub is member of the IPE/Board of Directors, the K-12 Sector Coordinator for the Canadian Union of Public Employees in British Columbia (CUPE BC Region) and a CUPE National Servicing Representative. Previously, Kirsten worked for over ten years for CoDevelopment Canada building international solidarity between unions and social justice organizations in Canada and Latin America.

Within weeks, he stopped entering the classroom. They called us daily, threatening to call 911 if we didn’t come quickly enough.

Within weeks, he stopped entering the classroom. They called us daily, threatening to call 911 if we didn’t come quickly enough. stretched thin. Children without formal diagnoses fall through the cracks. Parents fight for years to get their children diagnosed and then are told there are no resources to support them. Families feel like they are trapped in a cycle of bait and switch while our children are circling the drain.

stretched thin. Children without formal diagnoses fall through the cracks. Parents fight for years to get their children diagnosed and then are told there are no resources to support them. Families feel like they are trapped in a cycle of bait and switch while our children are circling the drain. School exclusion is a pipeline. It begins the moment a child is made to feel that their presence is conditional—that they are too much. And it compounds: in anxiety, in early police contact, in fractured families, in long-term reliance on disability supports.

School exclusion is a pipeline. It begins the moment a child is made to feel that their presence is conditional—that they are too much. And it compounds: in anxiety, in early police contact, in fractured families, in long-term reliance on disability supports. As the IPE quoted UNICEF Canada in our

As the IPE quoted UNICEF Canada in our

Having good food available at school would reduce busy families’ financial and time pressures, expose kids to a wide range of healthy foods, remove the stigma of current food programs that are targeted only to kids from poor families and support local food production.

Having good food available at school would reduce busy families’ financial and time pressures, expose kids to a wide range of healthy foods, remove the stigma of current food programs that are targeted only to kids from poor families and support local food production. and community members who participated in the hearings. From a school library in Gibsons, to an auditorium in McBride, to a community hall in Haida Gwaii, to high school classrooms in Fort St John, and many places and spaces in between- each session was highly engaging and deeply meaningful.

and community members who participated in the hearings. From a school library in Gibsons, to an auditorium in McBride, to a community hall in Haida Gwaii, to high school classrooms in Fort St John, and many places and spaces in between- each session was highly engaging and deeply meaningful. responsible life in a free and democratic society, to participate in a world which each generation will shape and build.”

responsible life in a free and democratic society, to participate in a world which each generation will shape and build.”

Obviously, anything that makes the well-heeled pay a little extra or tames profit-taking in the housing market should benefit the push for increased affordability.

Obviously, anything that makes the well-heeled pay a little extra or tames profit-taking in the housing market should benefit the push for increased affordability.