IPE/BC is an independent, non-partisan organization, however we recognize that IPE/BC Associates and guest authors hold a range of views and interests relative to public schools, education issues, and the political landscape in BC. Perspectives is an opportunity for Associates and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays.

Cost cutting dressed up as innovation? We have worries about hybrid learning.

August 28, 2025

By Moira Mackenzie, IPE/BC Board

The Surrey School Board made the decision to introduce a hybrid learning model for students in grades 10-12, establishing the option of a combination of online and in-person classes for students, as a pilot project for the 2025/26 school year. We can all recall when BC schools were closed and online learning was mandated as COVID was rapidly spreading in BC. At that time, this was a logical response to a very sudden, dangerous and widespread pandemic putting the lives of students, staff, and community members at risk. Online learning at that point was a well-meaning attempt to provide a safe learning alternative that would allow students to complete the year. However, the primary motivation for the decision to introduce a hybrid learning model this time has been well known and largely ignored by successive governments for many, many years. It’s based in the chronic underfunding of public education and the long term neglect of the pressing capital and operating needs in our public school system.

We know that the Surrey School Board among others has been actively lobbying for the district’s concerns to be addressed and we understand that, in the face of serious overcrowding, this decision may have felt less damaging than other responses. But we have concerns, both with the driving factors and the potential impacts, and we’re asking these questions:

- Will this decision alleviate the overcrowding?

Surrey’s serious overcrowding issues span the district and all grade levels. It’s alarming that, in a number of cases, enrolment in their neighbourhood school has been cut off to neighbourhood children and youth. When the enrollment cut off hit the news two years ago, the response of the then Minister was to let parents/caregivers know that they would be able to find a school somewhere else in the district in which to enrol their children.[i] It was not a very reassuring reply given the size of the district, the impact on families’ lives and means, and the importance of connecting children and youth in their communities. Yet it served to illustrate how serious the problem was becoming.

Surrey’s serious overcrowding issues span the district and all grade levels. It’s alarming that, in a number of cases, enrolment in their neighbourhood school has been cut off to neighbourhood children and youth. When the enrollment cut off hit the news two years ago, the response of the then Minister was to let parents/caregivers know that they would be able to find a school somewhere else in the district in which to enrol their children.[i] It was not a very reassuring reply given the size of the district, the impact on families’ lives and means, and the importance of connecting children and youth in their communities. Yet it served to illustrate how serious the problem was becoming.

Furthermore, the decision on hybrid delivery could well backfire as it removes from the province the on-going pressure to adequately fund capital costs and match the building of new schools with rapid population growth. Surrey is not alone in facing these overcrowding challenges. It may well become an expectation that all boards trying to secure approval for much needed new school buildings and help with the cost of portable classrooms, will be told to change their delivery models instead. And, while students are given the choice at this time, will it be mandated in the future, especially if it doesn’t go far enough in addressing overcrowding as is almost certainly the case?

Surrey currently has some 400 portable classrooms across the district. [ii]This has been described as roughly the equivalent of 16 new schools. The Ministry’s rules require that the cost of portables along with their set up and relocation be taken from Board’s operating funds. [iii]Surrey has already had to make significant cuts to their operating budget, including cutting 50 EA positions, closing learning centres, and eliminating the grade seven band program. The funding of more desperately needed portables would inevitably have meant more cuts.

- Is this an educationally sound decision?

Unfortunately, as with many decisions in the field of education, the driver is not the educational benefit or the likelihood of enhancing student success. It’s first and foremost about dollars and cents. We have too often seen cost-cutting measures dressed up as innovation. If our public schools are expected to do all they can to support student learning and focus on continuous improvement, and rightfully so, then the primary rationale for change has to be that it is in the student’s best interest, not that it saves space and money. Would the board have adopted this approach had it not been faced with a budget crunch, a burgeoning student population and a severe provincial backlog in the funding of new schools? It’s not at all likely.

We are not opposed to innovation- far from it! There have been countless educational decisions and innovations based on new understandings about how young people learn, how to support different learning styles and needs, and what values schools should reflect, to name just a few important drivers. Without the continual re-examination of teaching and learning, public schools would have been stuck in a time warp. However, we also have to think about the context for changes- while the expectations on schools have increased, the funding and support has declined. This is simply not sustainable, regardless of how much and how often the delivery model is changed.

We are not opposed to innovation- far from it! There have been countless educational decisions and innovations based on new understandings about how young people learn, how to support different learning styles and needs, and what values schools should reflect, to name just a few important drivers. Without the continual re-examination of teaching and learning, public schools would have been stuck in a time warp. However, we also have to think about the context for changes- while the expectations on schools have increased, the funding and support has declined. This is simply not sustainable, regardless of how much and how often the delivery model is changed.

- Will all students and their families/caregivers feel the impact equally?

At IPE/BC we believe that public education should provide students, regardless of their families’ means, with equal opportunities. It’s a fundamental reason for having a public education system and it’s in our collective interest as a society. We worry that this decision pre-supposes that all students have access to the necessary devices, appropriate learning spaces, readily available guidance and assistance, and more, and therefore all can consider the choice equally.

However, we know that, through no fault of their own, increasing numbers of parents/caregivers are struggling, doing their very best to cope with poverty, housing precarity, food insecurity, excessive work hours and multiple jobs, and much more. Online learning is not an equalizer; it shifts the responsibility for the educational environment and learning conditions onto parents/caregivers and underscores the growing gap in privilege and means in our society. Conversely public schools spaces help to mitigate these disparities and strive to provide equal opportunities.

- What might be the impact on student mental health and well-being?

The decline in mental health of children and youth is a grave concern here in BC and in other many other jurisdictions. The reasons  reported in studies vary and include isolation, social media and excessive time spent online, financial precarity and inequality, inadequate sleep levels, anxiety about climate change and other prevailing planetary issues, breakdown of community, and lack of supportive relationships. [iv] Public schools, combined with community supports, can certainly help turn this trend around when they have sufficient resources in place and students feel connected, valued and supported. We worry that increasing the time students spend online and away from the actual school community will work against their mental well-being.

reported in studies vary and include isolation, social media and excessive time spent online, financial precarity and inequality, inadequate sleep levels, anxiety about climate change and other prevailing planetary issues, breakdown of community, and lack of supportive relationships. [iv] Public schools, combined with community supports, can certainly help turn this trend around when they have sufficient resources in place and students feel connected, valued and supported. We worry that increasing the time students spend online and away from the actual school community will work against their mental well-being.

It’s also not lost on us that, when the school cell phone ban was mandated in BC, the rationale was that it would help keep students safe, supported and in school where they can learn and develop strong relationships. [v] Again, while the hybrid model is being offered as a choice at this point, will it become an expectation and work against the conditions that would otherwise support student wellness? And, will it also become a mandate expectation that takes the place of adequate education funding for in-school supports?

- Will this model help prepare students for the “real world” ahead?

Are we opposed to innovative projects and creative approaches in education? Certainly not! Innovation and resourcefulness are needed more than ever given the monumental issues our world is facing. But, so are the skills of learning to contribute within a community, engaging with others in person, forming positive relationships, collaborating and debating ideas, and understanding and valuing diversity. We think that is best achieved when learners come together in public schools and have the resources and support they need.

Yes, technology with the many options for online connections can be a very powerful, productive and engaging tool- one that can be effectively used for problem solving and learning. But we need to keep in mind that, whenever we hear it being said that young people need to learn how to cope in the “real world”, the speaker is inevitably projecting their biases and their vision of the real world, as if that vision was a universal truth, unalterable and the only choice. We have to step back and ask ourselves if today’s manifestation of a “real world” is something we want young people to replicate. Surely, we who have left monumental social issues, raging inequality, and the planet’s very survival to the real world to the next generations to solve should not be the one to declare what the real world for the next generation should be.

need to learn how to cope in the “real world”, the speaker is inevitably projecting their biases and their vision of the real world, as if that vision was a universal truth, unalterable and the only choice. We have to step back and ask ourselves if today’s manifestation of a “real world” is something we want young people to replicate. Surely, we who have left monumental social issues, raging inequality, and the planet’s very survival to the real world to the next generations to solve should not be the one to declare what the real world for the next generation should be.

Once again, we have to remember that this “solution” is being put forward in the context of budget shortfalls, years of cutbacks, and severely under-resourced public schools. We completely understand that boards are being driven to make decisions based on grossly inadequate funding; we know that trustees, parents, teachers, support staff, community members, and students themselves have been raising the concerns for many years. And, like them, we’re very worried for our public schools; they’re simply too important to our society a whole to be continually faced with losses. The situation in Surrey is but one example of a system under extreme pressure. It simply can’t continue.

[i] https://vancouver.citynews.ca/2024/03/20/surrey-schools-stop-enrolment/

[ii] https://globalnews.ca/news/11346020/surrey-portables-hybrid-remote-learning/

[iii] https://instituteforpubliceducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Placing-a-Priority-on-Public-Education.pdf

[iv]https://crhesi.uwo.ca/new-report-on-mental-health-inequalities-in-canada-key-insights-and-tools/,

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

[v] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/eby-schools-cellphone-1.7306551

Moira Mackenzie is member of the IPE/BC Board and a retired teacher with many years of experience in the Surrey and Cariboo Chilcotin school districts and in supporting teachers and public education as a member of BCTF staff.

Looking back to last March, Bryn recalled worrying about whether the resilience of students, teachers and parents could sustain itself for the long road ahead. However, even with very difficult challenges, shared leadership and strength have grown, with everyone working together in support of students, families, and the community. “This embodies what public education is all about- that it’s for the common good,” said Bryn. His hope is that distributed leadership with connections to community continues to flourish, post COVID-19.

Looking back to last March, Bryn recalled worrying about whether the resilience of students, teachers and parents could sustain itself for the long road ahead. However, even with very difficult challenges, shared leadership and strength have grown, with everyone working together in support of students, families, and the community. “This embodies what public education is all about- that it’s for the common good,” said Bryn. His hope is that distributed leadership with connections to community continues to flourish, post COVID-19. Jamie urged recognition of the Indigenous world view in schools, noting that Indigenous people are keepers of knowledge fundamental to the creation of a compassionate, harmonious society and to the planet’s very survival. She highlighted the need to recruit more Indigenous teachers and welcome Indigenous elders into classrooms, and expressed her concern that an over-emphasis on academics means that children are missing many of the basic life skills needed to survive and live in harmony with others. “We’re teaching kids to be scholars; we’re not teaching them to be community members,” she said.

Jamie urged recognition of the Indigenous world view in schools, noting that Indigenous people are keepers of knowledge fundamental to the creation of a compassionate, harmonious society and to the planet’s very survival. She highlighted the need to recruit more Indigenous teachers and welcome Indigenous elders into classrooms, and expressed her concern that an over-emphasis on academics means that children are missing many of the basic life skills needed to survive and live in harmony with others. “We’re teaching kids to be scholars; we’re not teaching them to be community members,” she said. “Every teacher sees the difficulty in it now and every parent sees the limitations,” said Julia. She noted that attendance at virtual meetings and workshops is high, but there is a passivity that comes with engaging online. “There is something about the physicality that leads to memorable professional development experiences and enhances the way we learn and make decisions together,” Julia observed.

“Every teacher sees the difficulty in it now and every parent sees the limitations,” said Julia. She noted that attendance at virtual meetings and workshops is high, but there is a passivity that comes with engaging online. “There is something about the physicality that leads to memorable professional development experiences and enhances the way we learn and make decisions together,” Julia observed. The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use.

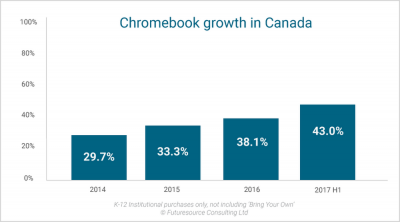

The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use. It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.

It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.

Technology on its own cannot improve education systems and require other elements to be functional and focus on the effective use of technology. Yet our education systems continue to invest in technology, often based on what seems to be the latest and greatest. How do we address this so that the education system can achieve the results we expect with current and innovative technology developments? How do we avoid our education becoming too influenced by the latest technology development and ‘carpet-baggers’ peddling the latest technology with promises to revolutionize education?

Technology on its own cannot improve education systems and require other elements to be functional and focus on the effective use of technology. Yet our education systems continue to invest in technology, often based on what seems to be the latest and greatest. How do we address this so that the education system can achieve the results we expect with current and innovative technology developments? How do we avoid our education becoming too influenced by the latest technology development and ‘carpet-baggers’ peddling the latest technology with promises to revolutionize education?

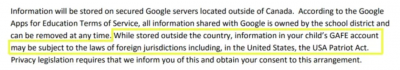

Thousands of apps for education have already been created. Development costs are often covered by venture capitalists. They invest in app development with the hope that future profits will provide a return on investment when it captures a significant number of users. In many cases, the return is the sale of information about the teachers and students using the app. It is the users themselves who are the source of profits when their data is sold.

Thousands of apps for education have already been created. Development costs are often covered by venture capitalists. They invest in app development with the hope that future profits will provide a return on investment when it captures a significant number of users. In many cases, the return is the sale of information about the teachers and students using the app. It is the users themselves who are the source of profits when their data is sold.