Perspectives is an opportunity for Fellows and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays. IPE/BC Fellows hold a range of views and interests relative to public education.

Claims about education costs mislead by ignoring social and educational changes

by Larry Kuehn

A claim about the history of funding of public education by UBC professor Jason Ellis is seriously misleading by omitting the context of changes that have taken place in education over the past fifty years. He has published an article in which he claims there has been an increase in spending on BC public education between 1970 and 2020 that he calculates as 250%. This increase is described as “astounding” according to Ellis, as quoted in a UBC press release, although he doesn’t use that phrase in his academic article.

Unfortunately, the article is an overly simplistic comparison of gross expenditures inflation adjusted with the number of students without looking at the changing expectations of education over five decades, the way the public schools have adjusted to meet those, and the very real costs of those changes. Ellis ignores the complexity when he says, “After all, if we are talking about how much we spend on K-12 schools, it surely matters how far those dollars stretch. That is mainly a question of how many students public schools need to educate at any given point in time.” (Ellis, p. 104) In fact, costs are a factor of not just how many students you have, but also the changing and diverse nature of student needs and what you offer them in the way of service and conditions.

point in time.” (Ellis, p. 104) In fact, costs are a factor of not just how many students you have, but also the changing and diverse nature of student needs and what you offer them in the way of service and conditions.

The study chooses an arbitrary date as the baseline, without identifying the context of the system at that time and the rationale for improvements in conditions and thus expenditures since then. The language of the article reflects a bias toward “cost control” and “fiscal discipline” and an opposition to the collective bargaining rights of teachers. The rationale for the article in the end seems to be a challenge to those who see the limitations on education expenditure as based on neoliberal ideology when the facts actually support claims of those who see neoliberal policies as having a negative impact on educational expenditures.

The educational conditions in the baseline of 1970

The choice of a baseline can have a significant effect—if one chooses a low point, then the increases seem greater–and 1970 was a low point for several reasons.

The number of students grew rapidly in the 1960s, but the system did not keep up with that growth. The W.A.C. Bennett Social Credit government had a priority on building dams for hydro and other infrastructure development rather than schools and in the late 1960s had introduced policies, including a school referendum system, to limit school district expenditures.

Double shifts were common, where two schools were run within one building, an early shift until mid-day and another in the afternoon until evening. Many schools had to be built at this time, but Ellis acknowledges that the amount in his 1970 baseline does not include capital costs of building schools, but those cost are included for the period after 1974.

Class sizes were large as well. B.C. had the largest classes in Canada in 1970, except for Newfoundland. The BC Teachers’ Federation ran a campaign at the time to limit class sizes to 40, an indication of the conditions, a situation that not only teachers but also parents would not find acceptable now. There were significant reductions in pupil-teacher ratios and class sizes in the 1970s, catching up with the limitations that existed in 1970. None of these improvements in the 1970s were the result of teachers’ collective bargaining since the legal framework at the time only allowed for negotiation of salaries and benefits.

The school system in 1970 was also much more elitist and exclusionary. While now we are not satisfied if fewer than 90% of students complete graduation, it was half that fifty years ago. Students with special needs were not included, few programs existed for students whose first language was not English, many Indigenous students were in Residential “Schools,” and many of the Indigenous students in the public system were marginalized and actively discouraged from staying after age 16. Being inclusive in addressing all these needs takes people and resources. Very few would be satisfied with the education system we offered in 1970. In fact, many would require more of our current system, not expecting that this could be achieved on 1970 funding levels.

students whose first language was not English, many Indigenous students were in Residential “Schools,” and many of the Indigenous students in the public system were marginalized and actively discouraged from staying after age 16. Being inclusive in addressing all these needs takes people and resources. Very few would be satisfied with the education system we offered in 1970. In fact, many would require more of our current system, not expecting that this could be achieved on 1970 funding levels.

Many teachers who retired before 1970 lived on pensions that left them in poverty. Governments in the previous fifty years had been unwilling to provide the financing for an adequate pension system, a situation that was finally addressed in the 1970s and beyond—at a necessary cost.

The teaching force in 1970 had much lower overall levels of qualifications that have been continually increasing over the decades. In 1970 many teachers at the elementary level had entered teaching with one year of university and a year of teacher education. Most of them increased their qualifications over time, often with many years of summer university courses. In contrast, now very few enter the profession with less than a degree as well as teacher education. At least a third of current teachers have a master’s degree or a diploma beyond their bachelor’s degree and teacher education. These qualifications reflect an ability to deal with a much more complex set of educational needs—and legitimately get reflected in increased costs.

Yes, costs have increased, as they have in most things. The percentage they have increased depends not just on what the costs are, but also the baseline on which you are making the comparisons. If you choose the baseline that is a low point, it will appear that the increase is greater—and after 1970 was a point when a lot of pent-up demands were increasing on the public education system in B.C.

Yes, costs have increased, as they have in most things. The percentage they have increased depends not just on what the costs are, but also the baseline on which you are making the comparisons. If you choose the baseline that is a low point, it will appear that the increase is greater—and after 1970 was a point when a lot of pent-up demands were increasing on the public education system in B.C.

The conservative framing of the article

Some of Ellis’s language draws from a source frequently referenced in the article, Thomas Fleming, a conservative B.C. education historian. Fleming’s ideal of education is based in what he calls the “imperial” age of education in B.C. when education policy was determined by the education officials in the ministry (then Department) of education. This handful of men (and they were always men) could determine policy for the system and carry it out through a network of inspectors. It could keep costs under control and keep the system narrowly focused on academic purposes, not the broader social demands.

Fleming acknowledged that pressure was growing in the system in the 1960s to expand the mandate and the services of the schools, even as the enrolment was growing dramatically, and women were becoming restive over their subservient role in the system. Fleming defines 1972 as the break point in the system with the election of the New Democrat government and the active role of the BCTF in the election. The ministry officials lost control and the system was open to influence by politicians, teachers through the BCTF and what he calls special interests—parents making demands for their children and social activists calling for marginalized groups to have their needs met. All these new demands on the system would require more resources.

Calling for a return to a narrower, less inclusive education system doesn’t have any credence. The public does not want the system to do less, but to do more of whatever particular concern they have. This is confirmed every time budget limitations lead to services being cut. Fleming tried to influence a call for a narrower system focus on the academic as an editor of the 1988 Royal Commission on Education Report, but was frustrated by the lack of response of the system to that recommendation. If a direct call to cut what the system does would not work, another approach is to call for reduced costs so it is not able to do as much.

cut. Fleming tried to influence a call for a narrower system focus on the academic as an editor of the 1988 Royal Commission on Education Report, but was frustrated by the lack of response of the system to that recommendation. If a direct call to cut what the system does would not work, another approach is to call for reduced costs so it is not able to do as much.

Here is where Ellis picks up Fleming’s approach using the language of “rein in educational spending” (p. 102); “cost control” (p. 102, 110, 111, 117, 118); “controlling spending” (p. 102, 113, 114); “impose spending limits” (p. 118); “fiscal discipline” (p. 113). Fleming is particularly critical of the BCTF influence in public education, beginning at the point that it became active in the 1972 election, and particularly after achieving collective bargaining rights in 1988 and Ellis adopts Flemings negative perspective on teacher bargaining. Fleming’s ideal was the “old boys network” of the education department that many BCTF leaders were a part of before the change in the organization about 1970.

Although Ellis contends that “saying that spending is up considerably is not saying it should not have increased. It is not saying that spending should not rise further in the future.” (p. 118) In only focusing on how much the expenditures have grown and not addressing the purposes of the increases or the services provided, and calling the increases “astounding”, Ellis plays into those who would use cost control to narrow educational offerings and who will use the headlines from his study to support their aims.

Reference

Ellis, Jason. (2021) “A Short History of K-12 Public School Spending in British Columbia, 1970-2020.” Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 196, 102-123.

Larry Kuehn is a member of the IPE/BC Board of Directors and chair of the Research and Programs Committee. He is a research associate for the CCPA and retired BCTF Director of Research and Technology. He has written extensively on education matters including funding, globalization, technology and privacy.

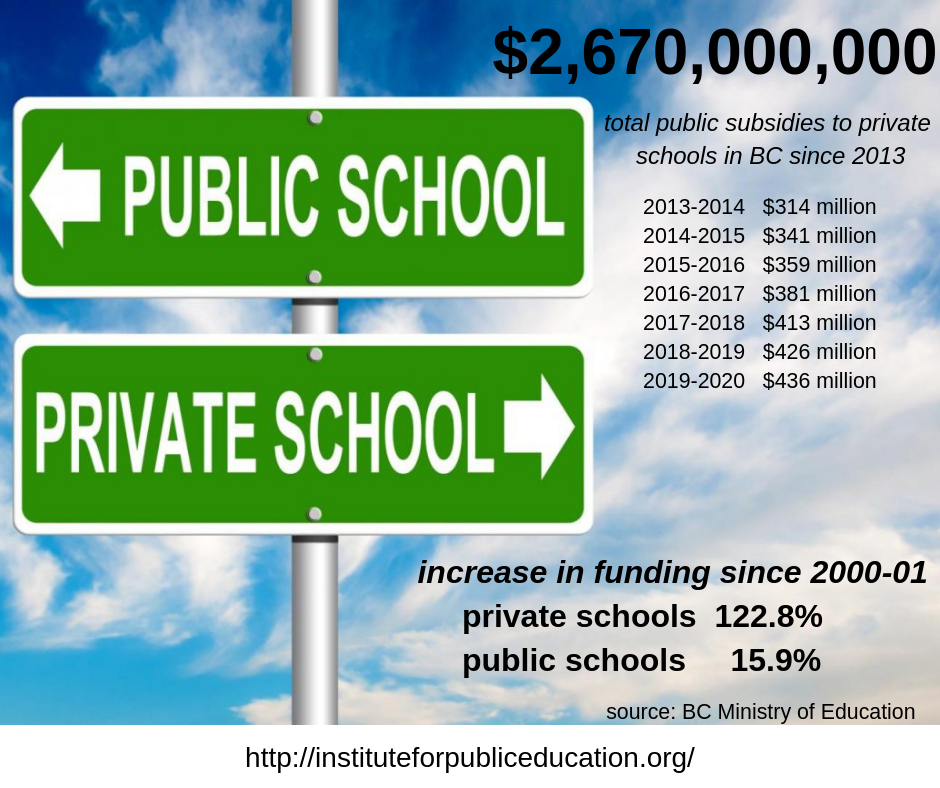

You can check out our analysis of public funding for private schools in BC, and our arguments for discontinuing these subsidies to private schools,

You can check out our analysis of public funding for private schools in BC, and our arguments for discontinuing these subsidies to private schools,

One such feature is school choice. “Choice” takes place in a variety of ways: the open catchment areas; allowing and increasing public funding of private schools; allowing school fees; and promoting niche schools and academies. With only limited opposition (from parents, teachers and school trustees) “choice” policies have changed the nature of BC’s public school system. The impact of these changes is that we are moving from a more comprehensive, equitable, neighbourhood and community oriented, publicly administered school system, towards a semiprivate, stratified and segregated system in which precious limited resources are increasingly allocated to a privileged minority.

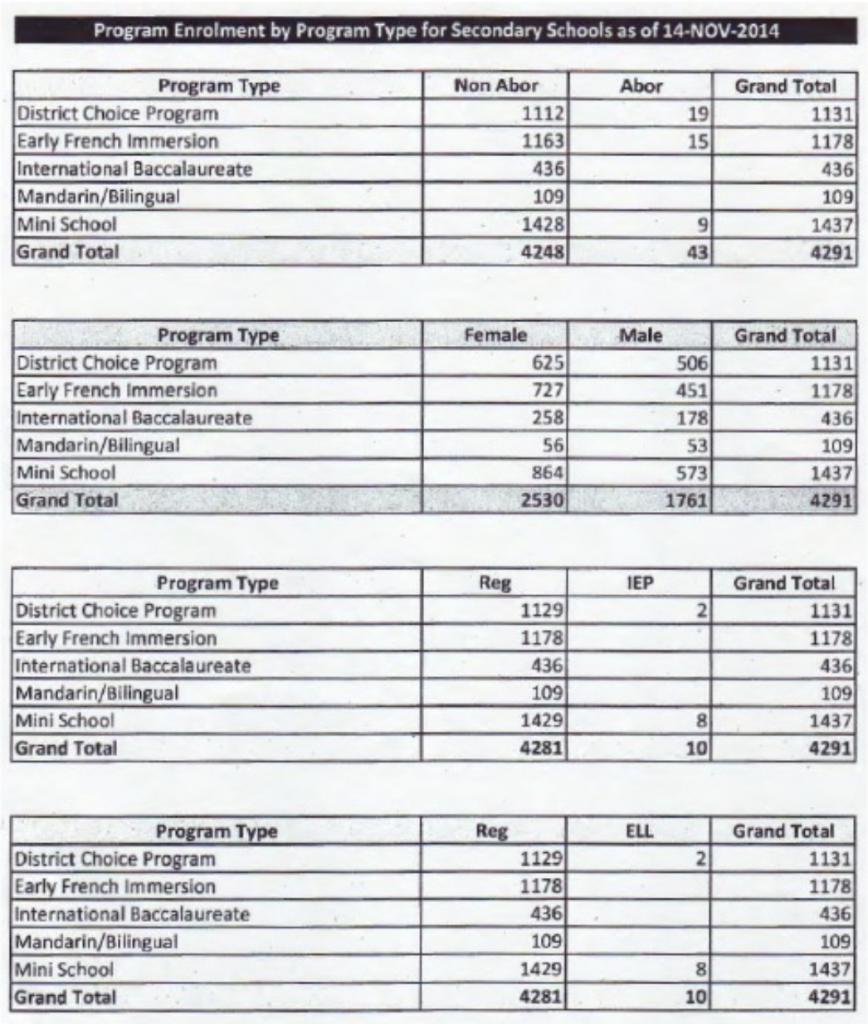

One such feature is school choice. “Choice” takes place in a variety of ways: the open catchment areas; allowing and increasing public funding of private schools; allowing school fees; and promoting niche schools and academies. With only limited opposition (from parents, teachers and school trustees) “choice” policies have changed the nature of BC’s public school system. The impact of these changes is that we are moving from a more comprehensive, equitable, neighbourhood and community oriented, publicly administered school system, towards a semiprivate, stratified and segregated system in which precious limited resources are increasingly allocated to a privileged minority. Yet another form of school choice is the Academy, or niche program. There are sports academies, and arts academies, but also academic academies such as International Baccalaureate programs, honours programs, and challenge programs. These

Yet another form of school choice is the Academy, or niche program. There are sports academies, and arts academies, but also academic academies such as International Baccalaureate programs, honours programs, and challenge programs. These  specialty programs often have competitive enrolment processes, and often require the payment of school fees (typically $2000 – $5000, but as much as $17,000/year). Thus, they are available only to a small subset of students.

specialty programs often have competitive enrolment processes, and often require the payment of school fees (typically $2000 – $5000, but as much as $17,000/year). Thus, they are available only to a small subset of students.

On December 7th, IPE/BC (with the support of Your Education Matters) held a Think Tank to discuss the wide range of issues around privatization in public education in British Columbia. IPE/BC Fellows, teachers, researchers, and community leaders came together to consider what issues to address and how strategically to do so. Joel French, Executive Director of

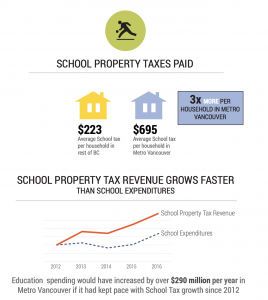

On December 7th, IPE/BC (with the support of Your Education Matters) held a Think Tank to discuss the wide range of issues around privatization in public education in British Columbia. IPE/BC Fellows, teachers, researchers, and community leaders came together to consider what issues to address and how strategically to do so. Joel French, Executive Director of  Obviously, anything that makes the well-heeled pay a little extra or tames profit-taking in the housing market should benefit the push for increased affordability.

Obviously, anything that makes the well-heeled pay a little extra or tames profit-taking in the housing market should benefit the push for increased affordability.