Perspectives is an opportunity for Fellows and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays. IPE/BC Fellows hold a range of views and interests relative to public education.

Moving beyond resistance to privatization

June 28, 2022

by Andrée Gacoin

What is the commercial mindset in public education? How do you see the commercial mindset in your school or district? What does privatization look like in your classroom? What does it mean to work together to resist the privatization of public education?

These are questions that 15 teachers, as well as invited guests from the Institute for Public Education, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, BC Ed Access, and the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation, engaged with as part of a day long think tank organised by the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation (BCTF) . The “Think Tank” is a methodology used by the BCTF as a form of activist research. Following Jones (2018), activist research is a “framework for conducting collaborative research that makes explicit challenges to power through transformative action” (p. 27). As such, the event aimed to create an interactive research space enabling dialogue and connection between teachers, academic or community stakeholders, and the union.

Resist…reclaim and rebuild

The Think Tank was structured to first identify key facets of privatization in British Columbia and then facilitate the development of strategies for action and resistance. The day’s conversations were interpreted in a visual mural, created by Sam Bradd of Drawing Change (see https://drawingchange.com/), a network of graphic recorders who listen, synthesize, and visually represent dialogue in real time.

The theoretical framing of the day was provided by Dr. Sam E. Abrams (2018), Director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education at Teacher’s College, Columbia University.

Dr. Abrams offers a way to analyse how the “commercial mindset” underpins the privatization of education and allows private interests to drive the direction of public education. For Abrams, this mindset has four key dimensions. Firstly, the libertarian critique is premised on the need for small government and doing the “minimum” within public services. Secondly, the drive towards commercial profit allows business models to be introduced into the provision of public education services. Thirdly, a sense of crisis creates the need for solutions to “fix” public education. Finally, public services are mired in a bureaucratic pathology which opens the way for external “solutions” by private “experts.”

Through discussion, the participants in the Think Tank took the mindset offered by Dr. Abrams into the lived realities of lived realities of privatization within public education. Their insights are organized around the key facets of the commercial mindset, while recognizing that they are continually overlapping and building on one another.

As highlighted in this IPE Occasional Paper, participants in the Think Tank theorized and developed, from the perspectives of BC teachers, strategies not only to resist privatization, but also reclaim and rebuild public education.

Changing the narrative

As schools look toward post-pandemic recovery, teacher unions and researchers are at a crucial junction in the defense of public education. Schools are key public spaces of collective learning and community care for children and youth. Privatization, in contrast, privileges individual and financial interests and undermines education as a public good.

Privatisation discourses position teachers as passive providers educational services. The BCTF Think Tank on Privatization provided a space for teachers to speak back to that assumption, weaving together a theoretical understanding of privatisation with their lived realities in classrooms and schools. This allowed space for concrete, teacher-led recommendations and actions for political organising and advocacy.

More broadly, the interactive research space created through the Think Tank offers a unique model for how academic and union researchers can work collaboratively. Unions, and the teachers they represent, are often framed as “sources” of data. For instance, the BCTF is frequently approached to circulate surveys created by external researchers, or to help recruit teachers as participants for interviews or focus groups. The Think Tank as a form of activist research foregrounds the voices and experiences of teachers and facilitates a shift from research on teachers to research with teachers, working together to fight for education as an equitably delivered public good.

Dr. Andrée Gacoin is the Director of the Information, Research and International Solidarity Division at the BC Teachers’ Federation and an IPE/BC Fellow. Her research focuses on developing a unique, in-depth and contextualized exploration of education in BC from the perspective of teachers. Andrée is particularly interested in using research as advocacy to uphold and strengthen an inclusive public education system.

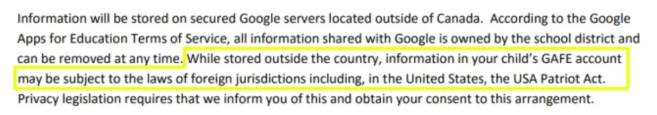

The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use.

The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use. It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.

It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.