Perspectives is an opportunity for Fellows and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays. IPE/BC Fellows hold a range of views and interests relative to public education.

The Community School Model- Just Imagine!

By David Chudnovsky

August 29, 2023

Imagine a small elementary school in a low income suburban community. The teachers are a mix of veterans and younger folks. It’s a really tough job as many of the students come to school hungry and have difficult home lives, but the teachers are enthusiastic and committed. Several of them have been teaching there for almost 30 years. They’ve all thought of looking for easier placements, but they can’t bring themselves to leave these kids.

There’s an evening program for adults – with courses in everything from belly dancing to introductory business skills to gymnastics – and there’s a ceramics studio with a kiln and slip and glazes that’s used by the kids during the day and adults at night.

There’s an evening program for adults – with courses in everything from belly dancing to introductory business skills to gymnastics – and there’s a ceramics studio with a kiln and slip and glazes that’s used by the kids during the day and adults at night.

Students work with a community curriculum developed by the teachers that reflects the experience of residents and neighbours.

Adult Basic Education classes are taught in a couple of empty classrooms during the day and in the kids’ classrooms in the evening – from basic literacy for people who can’t read or write to high school equivalency GED prep sessions. For more than 30 hours a week dozens of adults share the school with the elementary students.

A group of neighbourhood women meet in the school to organize a childcare centre and it’s just about to open in the community centre down the street.

A Community Newspaper is published four times a year through the school.

There’s a seniors group that meets monthly and organizes outings, and also arranges for older neighbours to volunteer in classrooms and interact with the elementary students.

In a portable in the parking lot behind the school is a re-entry program for teenagers who’ve been out of school for at least 6 months. The school recruits those students through local social service agencies, high school counselors and the media.

In a portable in the parking lot behind the school is a re-entry program for teenagers who’ve been out of school for at least 6 months. The school recruits those students through local social service agencies, high school counselors and the media.

During the summer, a day camp runs using the school building and its facilities.

There’s a lunch program. Volunteers from the neighbourhood come into the school to make sandwiches or hot dogs – but it’s hard to get the money to make the program permanent.

There’s a community program run out of the school called Shape Up. A couple of the Shape Up staff will help you renovate your house, clean out your garage, landscape your backyard or do any one of hundreds of home improvement projects that keep getting put off. But residents have to contribute. Some help with the actual work of the project at their home. Some store the tools. Some make lunch and dinner for the workers. One guy sharpens and repairs the tools.

There’s an annual fundraising fair at the school, but it has to be scheduled for social assistance cheque week. If it isn’t, there’s no money to raise. But when it is, the whole neighbourhood participates, they have a great time, and some funds are raised to support the programs.

The School Board employs a teacher to organize and facilitate all of this, plus a night school monitor (paid for out of the fees for the night school courses), and a part time secretary. However, the real leadership is provided by a Community Board made up of neighbourhood folks  who advise and decide on the various programs, advertise, and explain what’s going on at the school to their neighbours, and advocate to the School Board and other governments and agencies for the various programs and activities at the school. Some of them are parents of kids at the school. Some of them aren’t.

who advise and decide on the various programs, advertise, and explain what’s going on at the school to their neighbours, and advocate to the School Board and other governments and agencies for the various programs and activities at the school. Some of them are parents of kids at the school. Some of them aren’t.

Sound good? A bit too good to be true? Pie in the sky? Not at all. That program – with a lot more elements – existed and flourished in a North Surrey neighbourhood for decades. I was lucky enough to be the Community School Coordinator – the teacher hired by the Board to run the Community School Program for close to ten years, and while it was a hard job, it was enormously exciting.

Neighbourhoods with Community Schools knew, and still know, that they are certainly cost effective, but more important, they build cooperation, educational and social success, and resilience.

The Community School model – with different characteristics in communities with different needs – came to an end in Surrey in the late 1980’s as a result of yet another budget crisis. But it still exists in some jurisdictions.

What a wonderful experience – using school resources and space to meet community needs. Those elementary school students learned so much from the range of people who themselves benefited from the school’s programs. The kids learned they were part of a community. They learned they could build and strengthen their neighborhood. They learned that seniors, and adults learning to read and write, and the fellow who lived down the street and sharpened tools, were all important parts of their lives. They learned what it means to be a citizen.

While you’re thinking about what was, imagine what could be. What if we added a Community Health Clinic and a Social Services Office to that Community School? What if the School Board meetings were held in each Community School once a year? What if the local First Nations were part of and the programs at the School?

What if School Boards and the Province really understood the value of schools as part of the wider community, understood schools as the building blocks of stronger and more resilient communities? Imagine a renaissance of Community Schools across BC.

Just imagine.

David Chudnovsky worked in nursery, elementary and secondary schools and at the university level in England, Ontario and BC during his 35-year teaching career. He is a past-president of the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation and was an elected Member of the Legislative Assembly in British Columbia Legislature from 2005-2009. David is co-author of the Charter for Public Education.

The early warning indicators are already here. Community members without teacher qualifications are placed in some classrooms. A lack of teachers on call are available to fill in behind teachers away because of illness. Staff lose their planning time as they are pulled in to cover thousands of classes without their regular faculty member. Students with disabilities are sent home, deprived of their right to education because their specialist teachers are required to cover classes for missing colleagues.

The early warning indicators are already here. Community members without teacher qualifications are placed in some classrooms. A lack of teachers on call are available to fill in behind teachers away because of illness. Staff lose their planning time as they are pulled in to cover thousands of classes without their regular faculty member. Students with disabilities are sent home, deprived of their right to education because their specialist teachers are required to cover classes for missing colleagues. The BC government has recognized these other demands and has provided funding for increased training positions in health care, technology, and trades. However, education has been an afterthought, if a thought at all.

The BC government has recognized these other demands and has provided funding for increased training positions in health care, technology, and trades. However, education has been an afterthought, if a thought at all. It is past time for the government to recognize that public education, like health care, requires urgent attention to staffing shortages.

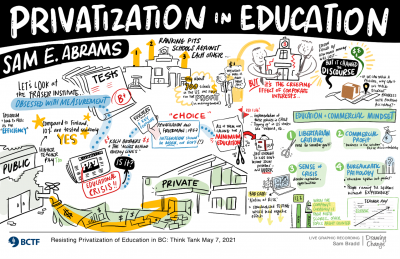

It is past time for the government to recognize that public education, like health care, requires urgent attention to staffing shortages. decline of nearly ten percent in government grants between 2006 and 2020. Annabree shone the light on the fact that this decline has led to risky decisions to seek varied sources of private dollars, which in turn has deprioritized the academic mission in favour of sponsored research. Additionally, it has fed the phenomenon of a burgeoning administration rather than a much needed increase in faculty to keep pace with the growth in student enrollment. Further, Annabree pointed out the folly in relying on revenue from international students to bolster budgets, as was made abundantly clear when the COVID pandemic diminished that revenue stream.

decline of nearly ten percent in government grants between 2006 and 2020. Annabree shone the light on the fact that this decline has led to risky decisions to seek varied sources of private dollars, which in turn has deprioritized the academic mission in favour of sponsored research. Additionally, it has fed the phenomenon of a burgeoning administration rather than a much needed increase in faculty to keep pace with the growth in student enrollment. Further, Annabree pointed out the folly in relying on revenue from international students to bolster budgets, as was made abundantly clear when the COVID pandemic diminished that revenue stream. on public education has been in significant decline. In 2001, BC allocated 2.8% to public schools while by 2021, it had reached an all-time low of 1.7%. Had the percentage even just remained steady throughout this period, there would have been an additional $2 billion more in school board budgets. Excessive cost-cutting, as Andree stated, is baked into the current structure of the funding model. We see this at play in yet another round of budget preparation this spring as numerous school boards are considering cuts once again, a reality that was simply not addressed in the provincial budget tabled and touted by the province in February.

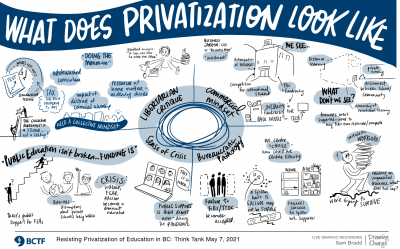

on public education has been in significant decline. In 2001, BC allocated 2.8% to public schools while by 2021, it had reached an all-time low of 1.7%. Had the percentage even just remained steady throughout this period, there would have been an additional $2 billion more in school board budgets. Excessive cost-cutting, as Andree stated, is baked into the current structure of the funding model. We see this at play in yet another round of budget preparation this spring as numerous school boards are considering cuts once again, a reality that was simply not addressed in the provincial budget tabled and touted by the province in February. adequate support leads to exclusion not inclusion. She has direct experience with the issues and, in her role with BCEdAccess, has spoken to many parents who feel their kids are not welcome in public schools. Due to underfunding and lack of appropriate supports, many students are being excluded from public schools and the full and appropriate range of learning experiences that should be available to them. BCEdAccess has been

adequate support leads to exclusion not inclusion. She has direct experience with the issues and, in her role with BCEdAccess, has spoken to many parents who feel their kids are not welcome in public schools. Due to underfunding and lack of appropriate supports, many students are being excluded from public schools and the full and appropriate range of learning experiences that should be available to them. BCEdAccess has been

participation. Too many take direction from their management teams, instead of the reverse. Far too much of the public’s business —and school board business is the public’s business — happens behind closed doors or in private emails instead of in public meetings, where it belongs.

participation. Too many take direction from their management teams, instead of the reverse. Far too much of the public’s business —and school board business is the public’s business — happens behind closed doors or in private emails instead of in public meetings, where it belongs.

Fortunately that’s a minority. I served eight years on the Vancouver School Board (VSB), and was chair for six of those. Many days started before dawn with live radio interviews and reading and replying to hundreds of emails. I would visit schools and attend meetings during the day, and spend afternoons preparing for evening meetings. My district had two formal board meetings a month in my day, along with five standing committees that met monthly, various briefing workshops and other internal and external committees where I represented the board as a liaison trustee, and frequent community events and speaking engagements.

Fortunately that’s a minority. I served eight years on the Vancouver School Board (VSB), and was chair for six of those. Many days started before dawn with live radio interviews and reading and replying to hundreds of emails. I would visit schools and attend meetings during the day, and spend afternoons preparing for evening meetings. My district had two formal board meetings a month in my day, along with five standing committees that met monthly, various briefing workshops and other internal and external committees where I represented the board as a liaison trustee, and frequent community events and speaking engagements. and are willing to stand up for it. We need trustees who understand the role and are willing to use it effectively, not just warm a seat at the board table.

and are willing to stand up for it. We need trustees who understand the role and are willing to use it effectively, not just warm a seat at the board table.

as an act of reconciliation,” recently sponsored by the BC Teachers’ Federation. The panel, moderated by BCTF President Teri Mooring, also included Peggy Janicki, who holds a seat designated for an Aboriginal teacher on the BCTF Executive Committee, and Brian Coleman, the chairperson of the BCTF Aboriginal Education Advisory Committee. Teri opened the session by describing official name changes as small but important steps in reconciliation and decolonization. She reflected on the impact of names on our understanding of people, place, and history, asking, “Whose lives and history do we honour and whose do we erase?”

as an act of reconciliation,” recently sponsored by the BC Teachers’ Federation. The panel, moderated by BCTF President Teri Mooring, also included Peggy Janicki, who holds a seat designated for an Aboriginal teacher on the BCTF Executive Committee, and Brian Coleman, the chairperson of the BCTF Aboriginal Education Advisory Committee. Teri opened the session by describing official name changes as small but important steps in reconciliation and decolonization. She reflected on the impact of names on our understanding of people, place, and history, asking, “Whose lives and history do we honour and whose do we erase?” After nearly a year of work, the committee came to a unanimous decision to propose that the school be named Skwo:wech, which is the Halq’eméylem word for “sturgeon.” The name is particularly significant given the connection with the Fraser River and the importance of sturgeon to Indigenous communities who traveled up and down the river.

After nearly a year of work, the committee came to a unanimous decision to propose that the school be named Skwo:wech, which is the Halq’eméylem word for “sturgeon.” The name is particularly significant given the connection with the Fraser River and the importance of sturgeon to Indigenous communities who traveled up and down the river. board stated, “It’s a name that we’re proud to move forward with, that came from a process that involved a great deal of collaboration and learning already, with more opportunities to build on for years to come.”

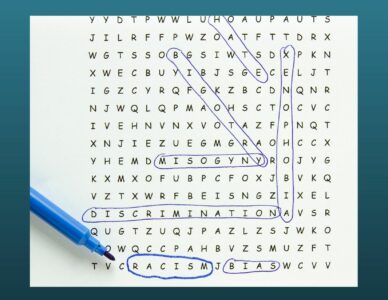

board stated, “It’s a name that we’re proud to move forward with, that came from a process that involved a great deal of collaboration and learning already, with more opportunities to build on for years to come.” The 19 months of the pandemic in B.C. have witnessed almost weekly incidents and events that point to the surge of racism both at a local and a provincial level, some minor, others with wider implications for sectors such as health, policing, education, sports, and politics. This very serious issue affects not just BC but the entire country. Yet, it was deeply disturbing that it was largely ignored during the recent federal election campaign. This, while we bore witness to the traumatic discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves of First Nations children at residential school sites.

The 19 months of the pandemic in B.C. have witnessed almost weekly incidents and events that point to the surge of racism both at a local and a provincial level, some minor, others with wider implications for sectors such as health, policing, education, sports, and politics. This very serious issue affects not just BC but the entire country. Yet, it was deeply disturbing that it was largely ignored during the recent federal election campaign. This, while we bore witness to the traumatic discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves of First Nations children at residential school sites. by students and parents who had the courage to speak out and use the BC human rights process. That’s one positive step; however, it took

by students and parents who had the courage to speak out and use the BC human rights process. That’s one positive step; however, it took  BC’s reckoning with racism is long overdue and we all have a role to play. The creation of a truly inclusive, just, respectful, and caring society needs urgent attention from all levels of government-local provincial and federal. Additionally, it is incumbent on each of us to speak out against racism and, in the context of our all-important public education system, insist that all schools and school districts are modeling the society we seek.

BC’s reckoning with racism is long overdue and we all have a role to play. The creation of a truly inclusive, just, respectful, and caring society needs urgent attention from all levels of government-local provincial and federal. Additionally, it is incumbent on each of us to speak out against racism and, in the context of our all-important public education system, insist that all schools and school districts are modeling the society we seek. Education policies have significant affects on individuals and the society as a whole and should be open to debate and reconsideration. Informed debate on policies can only take place if the relevant information is publicly available. This requires transparency on the part of government and local school authorities.

Education policies have significant affects on individuals and the society as a whole and should be open to debate and reconsideration. Informed debate on policies can only take place if the relevant information is publicly available. This requires transparency on the part of government and local school authorities.

Individuals will be less likely to file a request if they have to pay a fee, especially, like most of us, they are not experts at formulating a request in a way that will get the information they are looking for and might have to file multiple requests to get the information necessary.

Individuals will be less likely to file a request if they have to pay a fee, especially, like most of us, they are not experts at formulating a request in a way that will get the information they are looking for and might have to file multiple requests to get the information necessary. point in time.” (Ellis, p. 104) In fact, costs are a factor of not just how many students you have, but also the changing and diverse nature of student needs and what you offer them in the way of service and conditions.

point in time.” (Ellis, p. 104) In fact, costs are a factor of not just how many students you have, but also the changing and diverse nature of student needs and what you offer them in the way of service and conditions. students whose first language was not English, many Indigenous students were in Residential “Schools,” and many of the Indigenous students in the public system were marginalized and actively discouraged from staying after age 16. Being inclusive in addressing all these needs takes people and resources. Very few would be satisfied with the education system we offered in 1970. In fact, many would require more of our current system, not expecting that this could be achieved on 1970 funding levels.

students whose first language was not English, many Indigenous students were in Residential “Schools,” and many of the Indigenous students in the public system were marginalized and actively discouraged from staying after age 16. Being inclusive in addressing all these needs takes people and resources. Very few would be satisfied with the education system we offered in 1970. In fact, many would require more of our current system, not expecting that this could be achieved on 1970 funding levels. Yes, costs have increased, as they have in most things. The percentage they have increased depends not just on what the costs are, but also the baseline on which you are making the comparisons. If you choose the baseline that is a low point, it will appear that the increase is greater—and after 1970 was a point when a lot of pent-up demands were increasing on the public education system in B.C.

Yes, costs have increased, as they have in most things. The percentage they have increased depends not just on what the costs are, but also the baseline on which you are making the comparisons. If you choose the baseline that is a low point, it will appear that the increase is greater—and after 1970 was a point when a lot of pent-up demands were increasing on the public education system in B.C. cut. Fleming tried to influence a call for a narrower system focus on the academic as an editor of the 1988 Royal Commission on Education Report, but was frustrated by the lack of response of the system to that recommendation. If a direct call to cut what the system does would not work, another approach is to call for reduced costs so it is not able to do as much.

cut. Fleming tried to influence a call for a narrower system focus on the academic as an editor of the 1988 Royal Commission on Education Report, but was frustrated by the lack of response of the system to that recommendation. If a direct call to cut what the system does would not work, another approach is to call for reduced costs so it is not able to do as much. learning; by employers for preparing a skilled work force; and by judicial authorities for preparing law-abiding citizens. In the current context (of pandemic), educators have been asked to take on accountability for the physical and mental health of students as well. In short, schools have many constituencies they serve and for many diverse reasons, but most of these groups have very little agency to inform educator practices. Instead, government has largely taken on that authority.

learning; by employers for preparing a skilled work force; and by judicial authorities for preparing law-abiding citizens. In the current context (of pandemic), educators have been asked to take on accountability for the physical and mental health of students as well. In short, schools have many constituencies they serve and for many diverse reasons, but most of these groups have very little agency to inform educator practices. Instead, government has largely taken on that authority. This separation of schools and communities is a problem. The provincial government has worked to address the problem in part through the establishment of Parent Advisory Committees and regular parent satisfaction surveys. Here too, however, power sharing between the Province and parents remains largely symbolic, and has in many ways been used to further constrain educator authority. Across all aspects of governance, in BC the Provincial government has centralized almost all authority regarding the public education system.

This separation of schools and communities is a problem. The provincial government has worked to address the problem in part through the establishment of Parent Advisory Committees and regular parent satisfaction surveys. Here too, however, power sharing between the Province and parents remains largely symbolic, and has in many ways been used to further constrain educator authority. Across all aspects of governance, in BC the Provincial government has centralized almost all authority regarding the public education system. politicians, and anyone expressing an interest in education in BC). In 42 communities across BC, in large and small cities, rural and urban settings, and throughout the province by e-mail, the panel solicited testimony from British Columbians. The process was focused on aspirational outcomes for BC students and so focused around four over-arching questions:

politicians, and anyone expressing an interest in education in BC). In 42 communities across BC, in large and small cities, rural and urban settings, and throughout the province by e-mail, the panel solicited testimony from British Columbians. The process was focused on aspirational outcomes for BC students and so focused around four over-arching questions: