Perspectives is an opportunity for Fellows and others to share their ideas in short, accessible essays. IPE/BC Fellows hold a range of views and interests relative to public education.

The Charter for Public Education project: Reflections from a parent on the panel

By Kathy Whittam

My experience as a panel member for the Charter for Public Education was a crash course in how public education works in BC and the many ways in which each community in this province is unique.

It now seems like our Charter journey was a lifetime ago. My stepson was in elementary school at the time. Later, as he was graduating from high school, my daughter began kindergarten. So, my partner and I got to engage with public education all over again. With my daughter now only a few years from finishing high school herself, I can say that public education has been a vastly different experience for each of them. But the big picture perspective I acquired while serving on the Charter panel certainly helped me as I navigated the school years with both.

The Charter experience was profound. I still reflect on all that I learned from the students, teachers, parents, trustees, principals, and community members who participated in the hearings. From a school library in Gibsons, to an auditorium in McBride, to a community hall in Haida Gwaii, to high school classrooms in Fort St John, and many places and spaces in between- each session was highly engaging and deeply meaningful.

and community members who participated in the hearings. From a school library in Gibsons, to an auditorium in McBride, to a community hall in Haida Gwaii, to high school classrooms in Fort St John, and many places and spaces in between- each session was highly engaging and deeply meaningful.

Inevitably, the dialogues began with frustration about budget cuts, and the ways in which those in public education system were struggling as a result. But the discussion quickly turned to the goals of public education, the characteristics of an educated person and community, and what our public education system should be providing to learners of all ages. For me, it was always affirming to hear participants describe the role of education as being much broader than simply preparing students to be workers.

I have heard the Charter, created from these rich discussions, critiqued as “motherhood and apple pie” statements, but I struggle to see the problem with that. What could possibly be wrong with developing a positive vision of the public education system with the learners at the center, supported by a broad commitment by all to work together to help all learners reach their full potential?

How can the Charter be used for discussion and advocacy today? I believe it is still a powerful and effective tool, especially when we think about the pressing issues now facing us. The Charter includes the promise that, as a community, we will “prepare learners for a socially  responsible life in a free and democratic society, to participate in a world which each generation will shape and build.”

responsible life in a free and democratic society, to participate in a world which each generation will shape and build.”

For a truly sustainable future, we urgently need transformative action. It’s very important that all generations be involved in shaping and building a better “normal “than we have ever had before. This is a critical time, in fact, to explore the role of public education in preparing our kids for their part in creating that future.

The promises in the Charter are coupled with the expectation that government “be responsible for fully funding all aspects of a quality education”. What is meant by “fully fund” and “quality education”? Ideally, each community should have a community public school that:

- is lead by a principal who is welcoming, supports the staff team, and partners with the community to build connections and opportunities for students.

- has teachers and support staff who are passionate about helping their students learn and grow.

- has a library in which students can relax, read, and enhance their literacy skills.

- offers music, art, play & physical education to fully develop students intellectual, social, physical, and esthetic capacities.

- supports families who are struggling so every child is nourished and able to learn and have fun.

- is supported by trustees who advocate for the needs of their schools; and,

- is provided with funding to meet those needs, so that staff and parents do not have to keep spending valuable time on fundraising and worrying about what is needed next.

It was clear from the engagement in the hearings that talking about what quality education means to us is time very well spent. This was true then and is still the case today. Equally so, the funding to give every student the support they need is money very well invested. Further, I believe that no single top-down approach can meet the needs of every district or community. Instead, it’s time for us to define the quality and support we’re looking for from the bottom up. Just imagine the potential in community members working together on behalf of the public schools in their district, collaborating to build a needs-based budget, identifying priorities, and defining the ways in which public education is key to the well being of their children and youth and their community overall.

As you can see, the Charter project had a significant impact on me. I feel certain that this was also the case for the many people throughout BC who took the time to engage and share their perspectives. I believe that the powerful process and outcome, the Charter for Public Education, have a great deal of wisdom to offer us today.

Kathy Whittam was a member of panel that conducted hearings in many communities around BC and drafted the Charter for Public Education document and report. She is a parent in Vancouver and has a deep commitment to inclusive, quality public education and progressive community engagement.

The BCTF, after a discussion and debate that was not without controversy, decided to fund the initiative. Many teachers were not convinced that their resources should be used in this way. Why, they asked, should teachers pay for a commission would be independent of the Federation? Still, the project was eventually enthusiastically approved.

The BCTF, after a discussion and debate that was not without controversy, decided to fund the initiative. Many teachers were not convinced that their resources should be used in this way. Why, they asked, should teachers pay for a commission would be independent of the Federation? Still, the project was eventually enthusiastically approved. mandate of the Charter process. Rather, the panel determined to draw out the principles behind the pain. They decided to pose a number of questions to the participants in every hearing:

mandate of the Charter process. Rather, the panel determined to draw out the principles behind the pain. They decided to pose a number of questions to the participants in every hearing:

Looking back to last March, Bryn recalled worrying about whether the resilience of students, teachers and parents could sustain itself for the long road ahead. However, even with very difficult challenges, shared leadership and strength have grown, with everyone working together in support of students, families, and the community. “This embodies what public education is all about- that it’s for the common good,” said Bryn. His hope is that distributed leadership with connections to community continues to flourish, post COVID-19.

Looking back to last March, Bryn recalled worrying about whether the resilience of students, teachers and parents could sustain itself for the long road ahead. However, even with very difficult challenges, shared leadership and strength have grown, with everyone working together in support of students, families, and the community. “This embodies what public education is all about- that it’s for the common good,” said Bryn. His hope is that distributed leadership with connections to community continues to flourish, post COVID-19. Jamie urged recognition of the Indigenous world view in schools, noting that Indigenous people are keepers of knowledge fundamental to the creation of a compassionate, harmonious society and to the planet’s very survival. She highlighted the need to recruit more Indigenous teachers and welcome Indigenous elders into classrooms, and expressed her concern that an over-emphasis on academics means that children are missing many of the basic life skills needed to survive and live in harmony with others. “We’re teaching kids to be scholars; we’re not teaching them to be community members,” she said.

Jamie urged recognition of the Indigenous world view in schools, noting that Indigenous people are keepers of knowledge fundamental to the creation of a compassionate, harmonious society and to the planet’s very survival. She highlighted the need to recruit more Indigenous teachers and welcome Indigenous elders into classrooms, and expressed her concern that an over-emphasis on academics means that children are missing many of the basic life skills needed to survive and live in harmony with others. “We’re teaching kids to be scholars; we’re not teaching them to be community members,” she said. “Every teacher sees the difficulty in it now and every parent sees the limitations,” said Julia. She noted that attendance at virtual meetings and workshops is high, but there is a passivity that comes with engaging online. “There is something about the physicality that leads to memorable professional development experiences and enhances the way we learn and make decisions together,” Julia observed.

“Every teacher sees the difficulty in it now and every parent sees the limitations,” said Julia. She noted that attendance at virtual meetings and workshops is high, but there is a passivity that comes with engaging online. “There is something about the physicality that leads to memorable professional development experiences and enhances the way we learn and make decisions together,” Julia observed. Privacy is not only a key element of freedom, but key to the development of autonomy as a person. Young people need the space to explore and develop, without the pressure of surveillance that will affect them the rest of their lives.

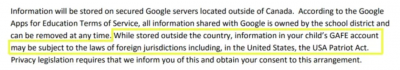

Privacy is not only a key element of freedom, but key to the development of autonomy as a person. Young people need the space to explore and develop, without the pressure of surveillance that will affect them the rest of their lives. protecting privacy and includes provisions that personal data not be held on servers outside of Canada. This is protection against invasive access provided by legislation elsewhere, particularly the U.S., where most data are held—although this protection was waived by Ministerial Order during the pandemic.

protecting privacy and includes provisions that personal data not be held on servers outside of Canada. This is protection against invasive access provided by legislation elsewhere, particularly the U.S., where most data are held—although this protection was waived by Ministerial Order during the pandemic. and expertise that should be available to the education system. The Privacy Commissioner should provide more guidance for the system on complying with the legislation and draw on international expertise available.

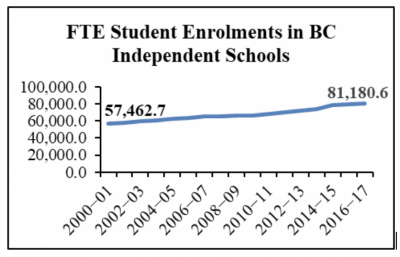

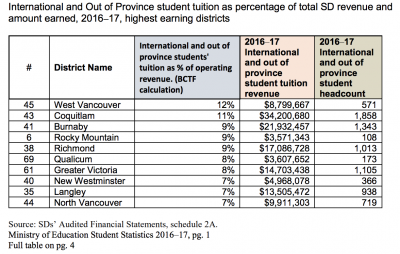

and expertise that should be available to the education system. The Privacy Commissioner should provide more guidance for the system on complying with the legislation and draw on international expertise available. One such feature is school choice. “Choice” takes place in a variety of ways: the open catchment areas; allowing and increasing public funding of private schools; allowing school fees; and promoting niche schools and academies. With only limited opposition (from parents, teachers and school trustees) “choice” policies have changed the nature of BC’s public school system. The impact of these changes is that we are moving from a more comprehensive, equitable, neighbourhood and community oriented, publicly administered school system, towards a semiprivate, stratified and segregated system in which precious limited resources are increasingly allocated to a privileged minority.

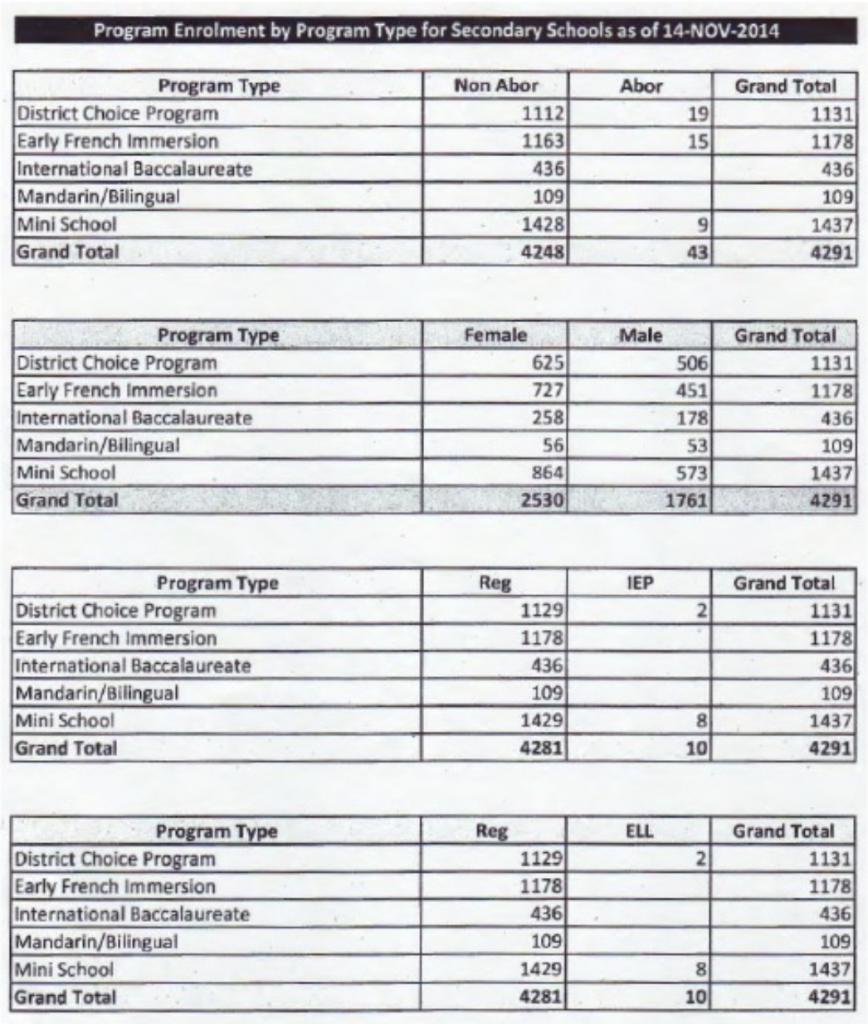

One such feature is school choice. “Choice” takes place in a variety of ways: the open catchment areas; allowing and increasing public funding of private schools; allowing school fees; and promoting niche schools and academies. With only limited opposition (from parents, teachers and school trustees) “choice” policies have changed the nature of BC’s public school system. The impact of these changes is that we are moving from a more comprehensive, equitable, neighbourhood and community oriented, publicly administered school system, towards a semiprivate, stratified and segregated system in which precious limited resources are increasingly allocated to a privileged minority. Yet another form of school choice is the Academy, or niche program. There are sports academies, and arts academies, but also academic academies such as International Baccalaureate programs, honours programs, and challenge programs. These

Yet another form of school choice is the Academy, or niche program. There are sports academies, and arts academies, but also academic academies such as International Baccalaureate programs, honours programs, and challenge programs. These  specialty programs often have competitive enrolment processes, and often require the payment of school fees (typically $2000 – $5000, but as much as $17,000/year). Thus, they are available only to a small subset of students.

specialty programs often have competitive enrolment processes, and often require the payment of school fees (typically $2000 – $5000, but as much as $17,000/year). Thus, they are available only to a small subset of students.

The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use.

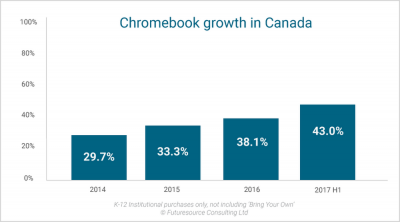

The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use. It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.

It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.

Technology on its own cannot improve education systems and require other elements to be functional and focus on the effective use of technology. Yet our education systems continue to invest in technology, often based on what seems to be the latest and greatest. How do we address this so that the education system can achieve the results we expect with current and innovative technology developments? How do we avoid our education becoming too influenced by the latest technology development and ‘carpet-baggers’ peddling the latest technology with promises to revolutionize education?

Technology on its own cannot improve education systems and require other elements to be functional and focus on the effective use of technology. Yet our education systems continue to invest in technology, often based on what seems to be the latest and greatest. How do we address this so that the education system can achieve the results we expect with current and innovative technology developments? How do we avoid our education becoming too influenced by the latest technology development and ‘carpet-baggers’ peddling the latest technology with promises to revolutionize education?