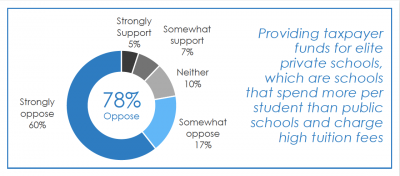

Vancouver, BC – The idea of public funding and subsidies for private schools in British Columbia is being met with disapproval from  residents across the province. A new poll finds that four-in-five British Columbians (78%) oppose providing taxpayer funds for elite or preparatory private schools in the province, with a total of 60% being strongly opposed to the idea.

residents across the province. A new poll finds that four-in-five British Columbians (78%) oppose providing taxpayer funds for elite or preparatory private schools in the province, with a total of 60% being strongly opposed to the idea.

The study was conducted by Insights West on behalf of the Institute for Public Education/British Columbia and First Call: BC Child and Youth Advocacy Coalition, with support from the Lochmaddy Foundation.

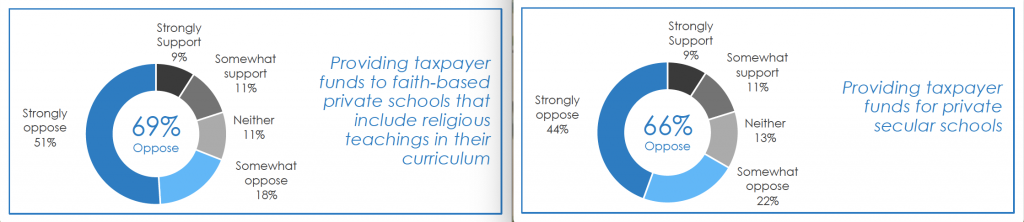

Government funding for religious or faith-based schools is opposed by 69% of British Columbians with 51% feeling strongly against the idea. And two-thirds (66%) oppose public funding for secular private schools with 44% in strong opposition. These sentiments are consistent across generations, genders and regions.

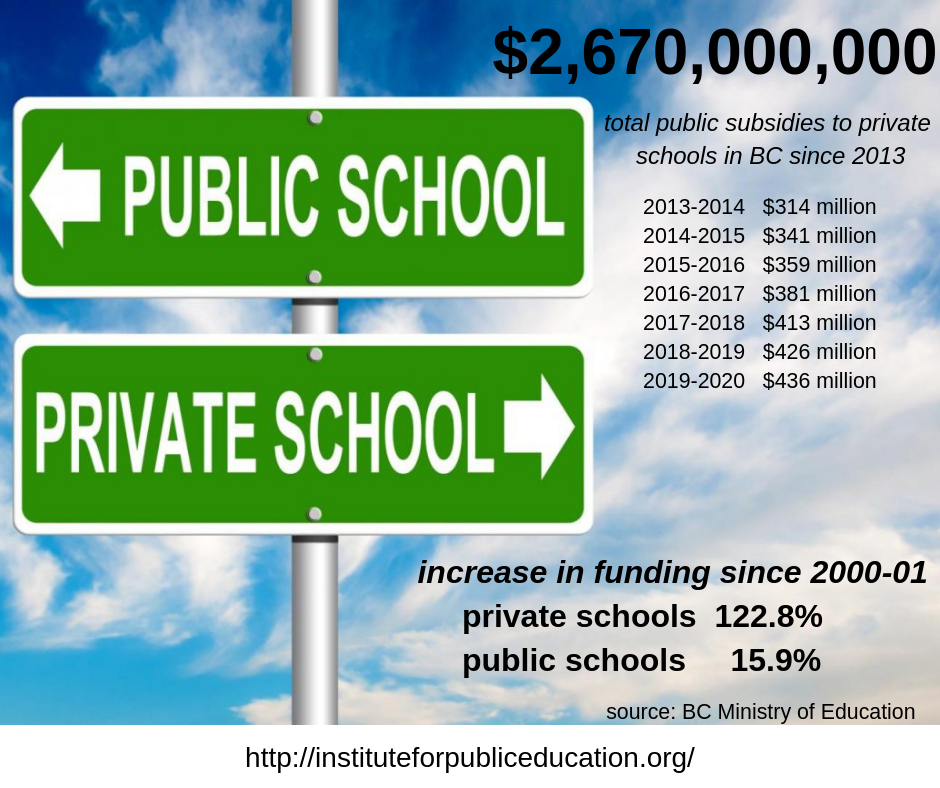

All private schools in the province receive public funding and most also charge additional tuition fees. Private schools that spend more per student than public schools receive 35% of the public school district per pupil cost, and those that spend the same or less per student as public schools receive 50% of the per pupil cost. In total, this outlay represents hundreds of millions of dollars annually from the provincial budget.

While provincial regulation and administration of private schools in British Columbia falls under the Independent Schools Act, private school employers in British Columbia are exempt from meeting the standards of the British Columbia Human Rights Code. That fact is mostly unknown by the BC public. According to the survey findings, only a very small percentage (10%) of respondents are aware that private schools in BC are exempt from the Code. Once made aware of this, a majority of respondents (81%) do not believe private schools should be allowed this exemption.

Likewise, nearly three-quarters (73%) of respondents from BC do not feel that private schools should be exempt from paying provincial property taxes, with 56% feeling strongly so. BCers are more accepting of granting tax benefits and credits for private donations to private schools. The survey reveals that 43% agree that donations to private schools should entitle the donor to an income tax credit while slightly less (38%) disagree, though 26% of respondents do feel strongly in that disagreement.

“Given the overwhelming opposition to public subsidies for elite private schools and the importance of adequately funding public education, the BC Ministry of Education should discontinue these subsidies immediately,” says Sandra Mathison, Executive Director of the Institute for Public Education BC. “This should be followed by a plan to phase out subsidies to faith-based schools as well.”

“Findings from this survey supports First Call’s position that adequate funding for public schools should be government’s priority,” commented Adrienne Montani, First Call’s Provincial Coordinator. “We need to ensure that all students, regardless of family income, can have their learning needs met at their local, public school.”

About the Survey:

Results are based on an online study conducted from May 13-20, 2019 among a representative sample of 817 British Columbians. The data has been statistically weighted according to Canadian census figures for age, gender and region. The margin of error—which measures sample variability—is +/- 3.4 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. Discrepancies between totals are due to rounding.

Click HERE to view the detailed data tabulations.

For further information, please contact:

Sandra Mathison, Executive Director

Institute for Public Education BC

publiceducationbc@gmail.com

604.879.7386

About Insights West:

Insights West is a progressive, Western-based, full-service marketing research company. It exists to serve the market with insights-driven research solutions and interpretive analysis through leading-edge tools, normative databases, and senior-level expertise across a broad range of public and private sector organizations. Insights West is based in Vancouver and Calgary.

About the Institute for Public Education BC:

The Institute for Public Education BC is an independent nonpartisan society providing high quality information and leadership to build a strong public education system for British Columbia’s children, families, and communities. IPE/BC offers analysis of current educational issues, supports public education, and shares current research findings to enrich dialogue on educational issues in British Columbia.

About First Call:

First Call: BC Child and Youth Advocacy Coalition is a non-partisan coalition of 105 provincial and regional organizations who have united their voices to put children and youth first in BC through public education, community mobilization, and public policy advocacy.

One such feature is school choice. “Choice” takes place in a variety of ways: the open catchment areas; allowing and increasing public funding of private schools; allowing school fees; and promoting niche schools and academies. With only limited opposition (from parents, teachers and school trustees) “choice” policies have changed the nature of BC’s public school system. The impact of these changes is that we are moving from a more comprehensive, equitable, neighbourhood and community oriented, publicly administered school system, towards a semiprivate, stratified and segregated system in which precious limited resources are increasingly allocated to a privileged minority.

One such feature is school choice. “Choice” takes place in a variety of ways: the open catchment areas; allowing and increasing public funding of private schools; allowing school fees; and promoting niche schools and academies. With only limited opposition (from parents, teachers and school trustees) “choice” policies have changed the nature of BC’s public school system. The impact of these changes is that we are moving from a more comprehensive, equitable, neighbourhood and community oriented, publicly administered school system, towards a semiprivate, stratified and segregated system in which precious limited resources are increasingly allocated to a privileged minority. Yet another form of school choice is the Academy, or niche program. There are sports academies, and arts academies, but also academic academies such as International Baccalaureate programs, honours programs, and challenge programs. These

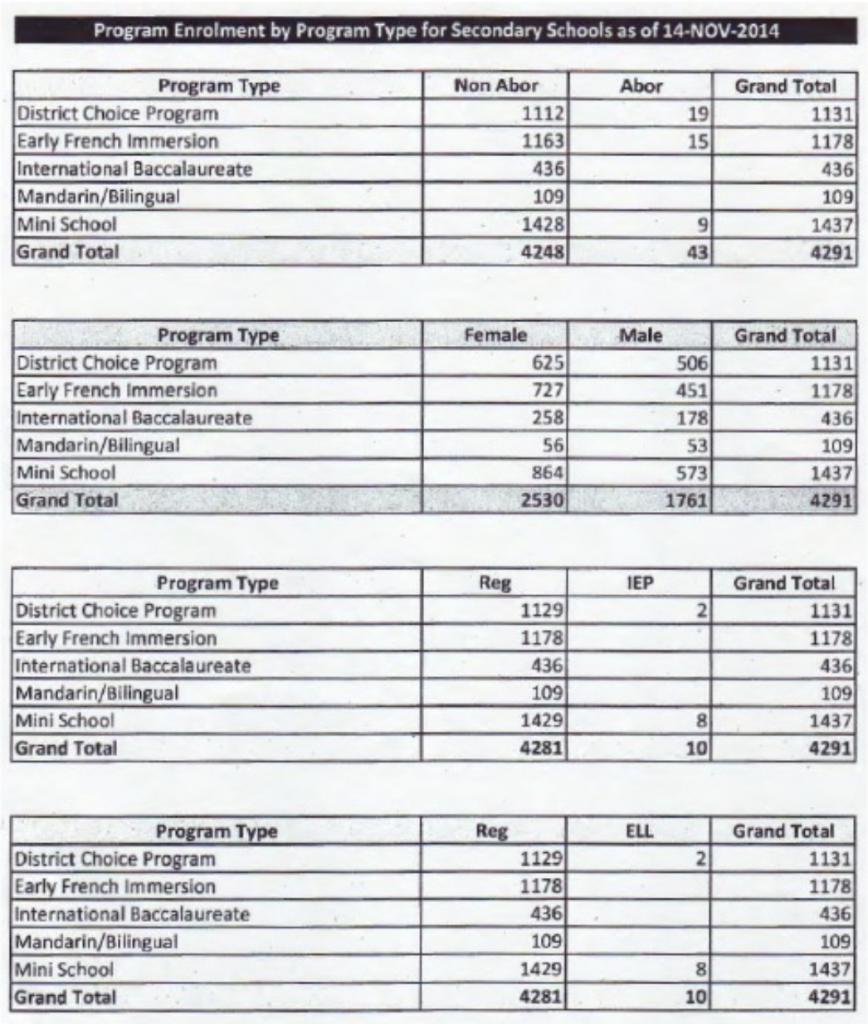

Yet another form of school choice is the Academy, or niche program. There are sports academies, and arts academies, but also academic academies such as International Baccalaureate programs, honours programs, and challenge programs. These  specialty programs often have competitive enrolment processes, and often require the payment of school fees (typically $2000 – $5000, but as much as $17,000/year). Thus, they are available only to a small subset of students.

specialty programs often have competitive enrolment processes, and often require the payment of school fees (typically $2000 – $5000, but as much as $17,000/year). Thus, they are available only to a small subset of students.

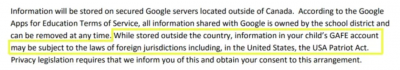

The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use.

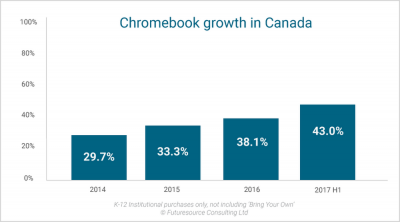

The most successful colonizer has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. Canada is fast approaching the same level of use. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked to student use. It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.

It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate is supplied by Google in the cloud—operating software, applications and memory. No need to build those into the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and are marketed globally.

On December 7th, IPE/BC (with the support of Your Education Matters) held a Think Tank to discuss the wide range of issues around privatization in public education in British Columbia. IPE/BC Fellows, teachers, researchers, and community leaders came together to consider what issues to address and how strategically to do so. Joel French, Executive Director of

On December 7th, IPE/BC (with the support of Your Education Matters) held a Think Tank to discuss the wide range of issues around privatization in public education in British Columbia. IPE/BC Fellows, teachers, researchers, and community leaders came together to consider what issues to address and how strategically to do so. Joel French, Executive Director of